The human spirit, throughout its long history, has always sought to understand the world, its mysteries, and the forces that govern life and death. Before the advent of modern science or monotheistic faiths, ancient peoples wove intricate narratives to explain the inexplicable, to find meaning in the cycles of nature, and to articulate their hopes and fears. Among the most profound and enduring of these traditional stories is the "Descent of Inanna," a myth born from the fertile crescent of Mesopotamia, echoing through the millennia in various forms, including those preserved as "Songs of Nineveh." It is a testament to the power of human imagination and a rich cultural artifact, presented here purely for its historical, educational, and cultural significance, not as a subject for belief or practice.

Origins and Cultural Background: The Cradle of Civilization

This compelling tale originates from ancient Sumer, the earliest known civilization in Mesopotamia, a region roughly corresponding to modern-day Iraq. Flourishing from around 4500 BCE, the Sumerians laid the foundations for many subsequent Near Eastern cultures, including the Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians. It was in cities like Uruk, Ur, and Lagash that this myth first took shape, etched onto clay tablets in cuneiform script. Later, as empires rose and fell, the story of Inanna was adapted and reinterpreted by successive cultures, with the Akkadians calling her Ishtar, and their versions forming part of the vast library of King Ashurbanipal in Nineveh, hence the enduring reference to "Songs of Nineveh."

The cultural era of ancient Sumer was defined by a polytheistic worldview, where a pantheon of gods and goddesses personified every aspect of existence. Life revolved around the mighty rivers Tigris and Euphrates, whose unpredictable floods brought both life-giving silt and devastating destruction. Agriculture was paramount, and the well-being of the city-states was seen as directly dependent on the favor of the deities. The Sumerians viewed the world as a complex tapestry woven by divine hands, with gods controlling the heavens, earth, and the dreaded underworld. They believed that humanity’s purpose was to serve the gods, to build temples, offer sacrifices, and maintain cosmic order through ritual. Death was an inevitable journey to a shadowy, dust-filled realm known as Kur or the Land of No Return, a place from which few ever returned.

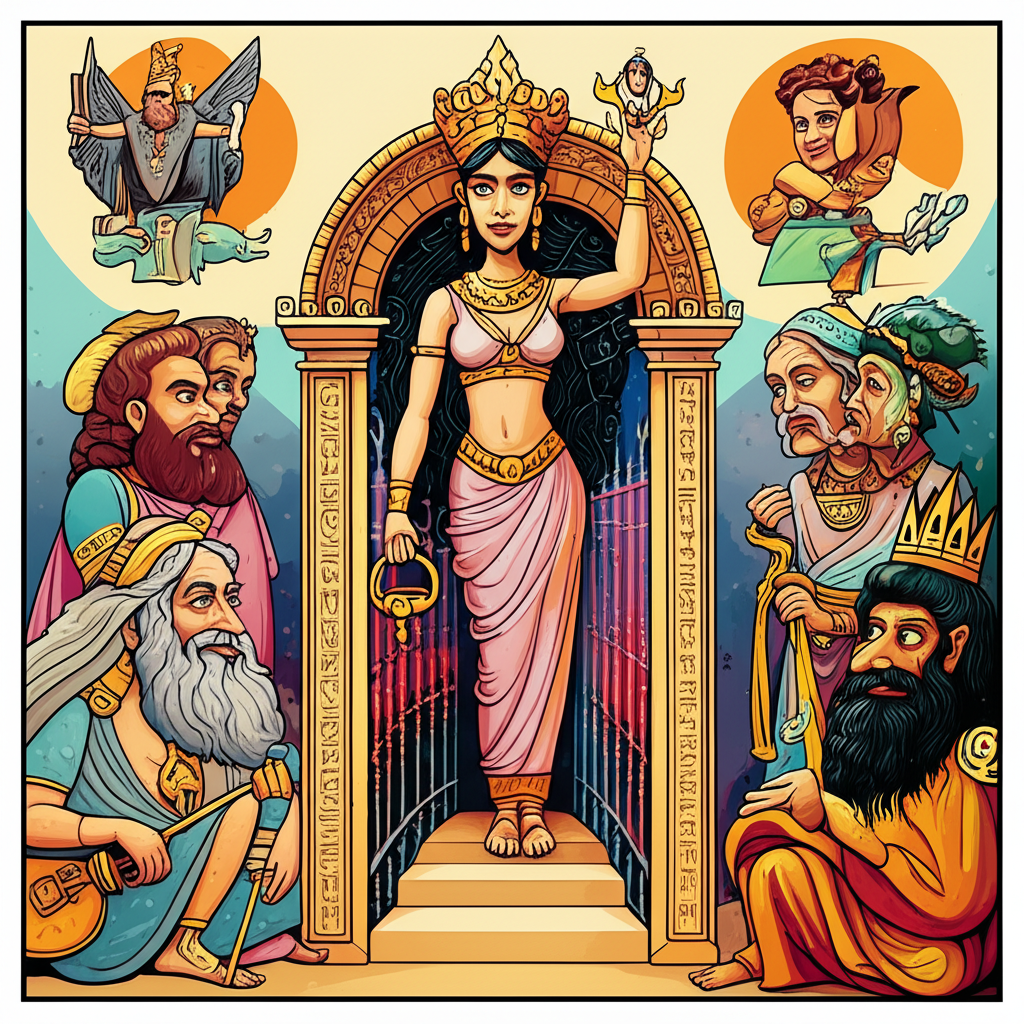

Inanna: Goddess of Contradictions

At the heart of this ancient narrative stands Inanna, one of the most prominent and complex deities in the Sumerian pantheon. Often depicted as a fierce lioness or a star, her symbolic attributes reflect her multifaceted nature. She was revered as the goddess of love, beauty, and sexual desire, embodying the life-giving force of nature and human passion. Yet, she was equally a formidable goddess of war, strategy, and political power, leading armies into battle and dictating the fate of kings. She carried the shugurra, the crown of the steppe, symbolizing her sovereignty, and her symbol was often a bundle of reeds tied into a loop, representing the gatepost of a sheepfold.

Inanna’s character is a study in paradox: she is both nurturing and destructive, fertile and fearsome, a bringer of both joy and sorrow. To the Sumerians, she embodied the raw, untamed power of the feminine principle, capable of immense creation and terrible wrath. It is crucial to remember that these descriptions are of a mythological figure, an imaginative construct used by ancient people to articulate their understanding of the world’s dualities, not a being to be worshipped or believed in as a divine entity.

The Journey to the Land of No Return: A Narrative Retelling

The myth of Inanna’s Descent begins with the goddess making a momentous, and seemingly inexplicable, decision: to journey to the underworld, the domain of her elder sister, Ereshkigal, the Queen of the Great Earth. Her stated purpose in some versions is to attend the funeral rites of Gugalanna, Ereshkigal’s bull-husband, while other interpretations suggest a desire to conquer the realm of the dead or to simply challenge its inexorable laws.

Before embarking on this perilous journey, Inanna meticulously adorns herself with all the symbols of her divine power: the shugurra crown, her lapis lazuli necklace, twin breast-plates, a gold ring, a measuring rod and line, and her royal robe. She then instructs her faithful minister, Ninshubur, that if she does not return after three days and three nights, he is to seek aid from the great gods of the heavens – Enlil, Nanna, and ultimately, Enki, the god of wisdom.

Inanna arrives at the outer gate of the underworld, guarded by Neti, the chief gatekeeper. She demands entry, declaring herself the "Queen of Heaven" and asserting her right to pass. Neti, however, is bound by the ancient laws of the underworld. He consults Ereshkigal, who, filled with bitterness and rage over her sister’s visit (perhaps seeing it as an intrusion or a challenge to her desolate sovereignty), instructs Neti to admit Inanna, but only according to the strict rites of the underworld.

Thus begins Inanna’s stripping away. As she passes through each of the seven gates of the underworld, Neti demands that she remove one piece of her divine attire, one symbol of her power. At the first gate, her shugurra crown is taken; at the second, her earrings; at the third, her lapis lazuli necklace; at the fourth, her twin breast-plates; at the fifth, her gold ring; at the sixth, her measuring rod and line; and finally, at the seventh gate, her royal robe. With each item surrendered, Inanna is divested of her status, her glory, and her protective magic, becoming increasingly vulnerable and human-like.

Naked and diminished, she finally enters the throne room of the underworld. There, Ereshkigal sits, surrounded by the Anunnaki, the fearsome judges of the dead. Ereshkigal fixes her "eye of death" upon Inanna, and the Anunnaki declare their verdict. Inanna, now stripped of all divine protection, is turned into a corpse, a piece of rotting meat, and hung upon a hook on the wall. The Queen of Heaven, the goddess of life, love, and war, is utterly vanquished in the realm of death.

Three days and three nights pass. True to her word, Ninshubur, finding Inanna has not returned, mourns her absence and journeys to the great gods. Enlil and Nanna, fearing the contagion of the underworld, refuse to help. But Enki, the wise and cunning god, is moved by Inanna’s plight. He scrapes dirt from under his fingernails and molds two sexless beings, the kurgarra and the galatur, creatures impervious to the laws of the underworld. He instructs them to descend, to empathize with Ereshkigal’s suffering (for she is constantly in pain and mourning), and to beg for Inanna’s corpse.

The kurgarra and galatur descend into the darkness, finding Ereshkigal in her anguish. They echo her groans, soothe her cries, and show her genuine compassion. Moved by their empathy, Ereshkigal grants them a boon. They request the corpse of Inanna. Ereshkigal agrees, and the two beings are given the rotting body. They sprinkle it with the food of life and the water of life, and miraculously, Inanna is revived.

But the laws of the underworld are immutable: no one returns without a substitute. As Inanna ascends from the depths, she is accompanied by a host of terrifying galla, demons of the underworld, who demand a replacement. They follow her through the cities of Sumer, ready to seize anyone Inanna designates. She passes by her grieving minister Ninshubur and her lamenting sons, but she will not condemn those who mourned for her.

Finally, she arrives in her own city, Uruk. There, upon her throne, she finds her husband, Dumuzid, the shepherd king, not mourning her absence but feasting and celebrating, adorned in rich garments. Overcome with fury and a sense of profound betrayal, Inanna fixes her "eye of death" upon him and points him out to the galla. "Take him!" she commands.

Dumuzid, terrified, attempts to flee, transforming into various animals with the help of the sun god Utu, Inanna’s brother. But the galla are relentless. They capture him and drag him down to the underworld. However, in a poignant twist, Dumuzid’s loyal sister, Geshtinanna, offers to take his place for half the year. Thus, the cycle is established: Dumuzid spends six months in the underworld, and Geshtinanna spends the other six, ensuring that neither is eternally trapped in the realm of the dead.

Symbolism and Meaning: Ancient Insights

To the ancient Sumerians, the "Descent of Inanna" was far more than a thrilling narrative; it was a profound tapestry of symbolic meaning. Primarily, it represented the cycle of death and rebirth inherent in the natural world. Inanna’s journey mirrored the yearly death of vegetation during the harsh Mesopotamian summer and its vibrant return with the autumn rains, a crucial concept for an agricultural society. Her descent and return symbolized the renewal of life, fertility, and the perpetual rhythm of the seasons.

It also explored the inescapability of mortality and the confrontation with the shadow self. Even a powerful goddess could not escape the domain of death without sacrifice. The stripping of Inanna’s garments at each gate symbolized the shedding of worldly power, status, and even the physical self, preparing one for the ultimate vulnerability of death. Her transformation into a corpse underscored the universal experience of decay.

The myth further delves into themes of sacrifice, redemption, and betrayal. Ninshubur’s loyalty and Enki’s wisdom represent the possibility of intervention and salvation. Dumuzid’s betrayal highlights the consequences of self-interest and the demand for accountability, even from those close to the divine. The cyclical exchange of Dumuzid and Geshtinanna signifies a form of redemption and the enduring bond of family, albeit one born from necessity.

Modern Perspectives: An Enduring Legacy

Even today, millennia after its inscription, the "Descent of Inanna" continues to captivate and resonate, finding new interpretations in modern thought. In literature and cultural studies, it is recognized as one of the earliest and most complete examples of a katabasis (a journey to the underworld), a narrative archetype that influences countless later myths, epics, and stories, from the Greek myths of Orpheus and Persephone to Dante’s Inferno and modern fantasy novels.

Psychologically, particularly through the lens of Jungian archetypes, Inanna’s journey is seen as a powerful metaphor for the process of individuation – the ego’s confrontation with the unconscious, the necessary descent into the "shadow" aspects of the self for ultimate transformation and integration. Feminists have embraced Inanna as an archetype of a strong, independent female deity who challenges patriarchal structures, even in the realm of death, and reclaims her power, albeit at a cost. Her story inspires discussions on female agency, sacrifice, and the complexities of divine femininity. Elements of her myth have subtly influenced popular culture, appearing in various forms of art, music, and even video games that explore themes of rebirth, sacrifice, and journeys through underworlds.

Conclusion: A Cultural Heritage

The "Descent of Inanna: Songs of Nineveh" stands as a magnificent testament to the enduring human capacity for storytelling and the profound wisdom embedded in ancient narratives. It is a vibrant thread in the rich tapestry of human cultural heritage, offering insights into the worldview, fears, and hopes of a civilization long past. We recognize these stories not as literal truths or objects of veneration, but as products of human imagination, crafted to make sense of a complex world and to transmit values and understanding across generations.

As Muslims, we firmly believe that Allah (SWT) is the one true Creator and Sustainer of all existence, the Almighty, the All-Knowing, and that He is utterly unique and incomparable. The narratives of ancient mythologies, while fascinating for their cultural and historical depth, are distinct from the divine truths revealed through prophets. They serve as a powerful reminder of the diverse ways humanity has sought to grapple with fundamental questions of life and death, purpose and destiny, before the light of monotheism illuminated the path. This myth, therefore, invites us to reflect on the universal human experience of seeking meaning, the power of imagination, and the timeless tradition of storytelling that connects us all through the echoes of ancient voices.