1. Introduction

Within the rich tapestry of ancient Roman mythology, stories of gods, heroes, and the very foundation of their mighty city were woven, passed down through generations. One such narrative, steeped in both resourcefulness and profound conflict, is the tale often referenced as "Bacchus and the War of the Rape of the Sabines." This traditional story, originating from the heart of early Roman culture, is a legend told by ancient people to explain the origins of their society, its people, and the often-brutal realities of nation-building. It is crucial to understand that this account is a myth, a product of human imagination from antiquity, not a factual historical event, and certainly not something to be believed, worshipped, or practiced in any real sense. We explore it here purely for its cultural, historical, and educational value, offering insight into the worldview of its originators.

2. Origins and Cultural Background

The myth of the Sabine Women finds its roots in the nascent period of the Roman Republic, a time when the burgeoning city-state was striving to establish its identity and secure its future. Ancient Roman society was deeply hierarchical, patriarchal, and fundamentally concerned with lineage, honor, and the continuation of the family (gens) and the state. Their worldview was animistic and polytheistic, populated by a vast pantheon of gods and goddesses who influenced every aspect of life, from the harvests to warfare, from love to death. Founding myths, like that of Romulus and Remus and the subsequent tale of the Sabine Women, were not merely stories; they were foundational narratives that legitimized Roman power, explained their customs, and instilled a sense of shared heritage and destiny among its citizens.

In this era, the concept of a "city" was tied to its ability to sustain itself and grow. A city without women, and thus without children, was a city doomed to extinction. The struggle for survival and the establishment of a lasting legacy were paramount concerns, shaping the decisions and actions of their legendary founders. The Romans believed their destiny was guided by divine will, and even their most audacious acts were often framed as being, in some way, sanctioned or influenced by the gods.

3. Character Descriptions

To fully appreciate this complex narrative, it is important to understand the key figures and their symbolic attributes:

-

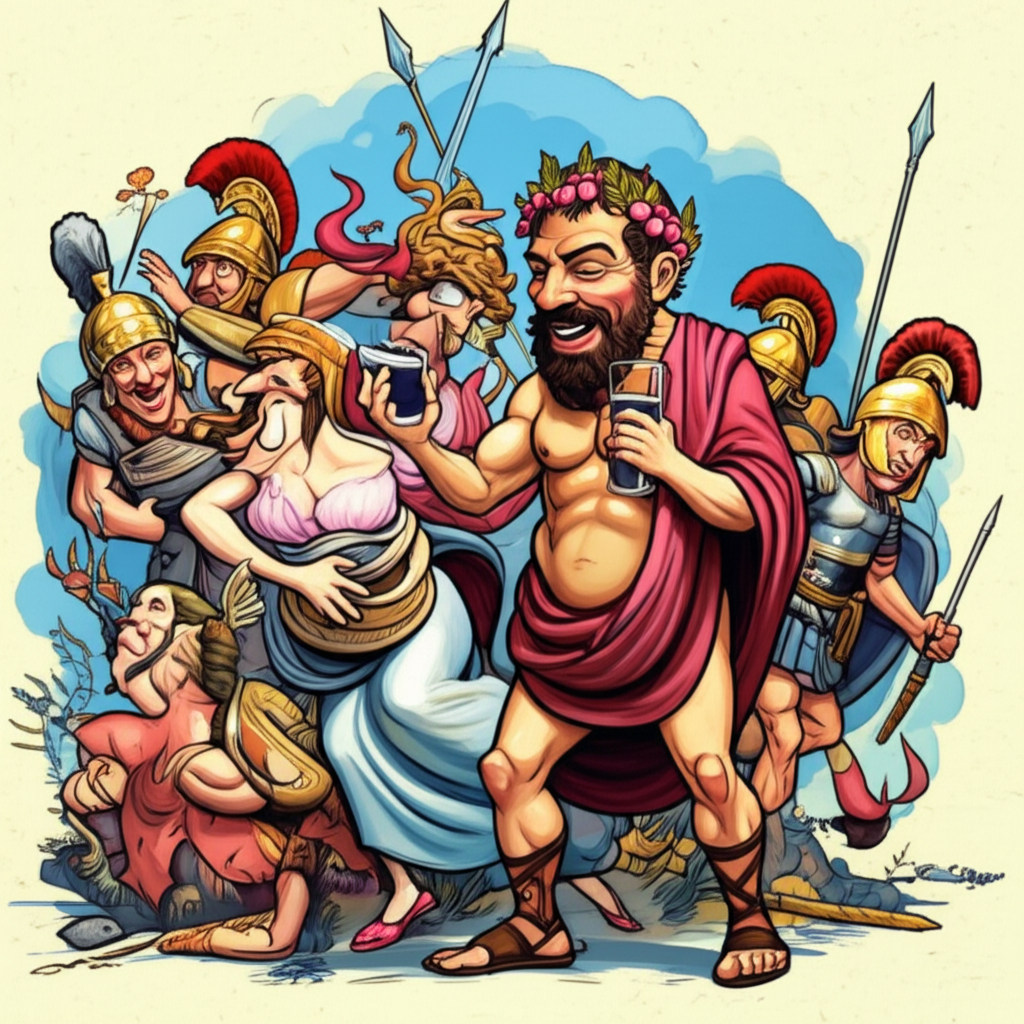

Bacchus (Dionysus in Greek Mythology): Though not a direct instigator of the conflict, Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, revelry, fertility, ecstasy, and theatrical madness, casts a significant symbolic shadow over the events. Often depicted with a thyrsus (a staff wrapped in ivy and topped with a pine cone), wearing ivy wreaths, and surrounded by maenads (his female followers) and satyrs, Bacchus represents liberation from convention, the intoxicating power of nature, and the raw, untamed aspects of human desire and emotion. His domain encompasses both the joyous abandon of festivals and the potentially destructive forces unleashed when inhibitions are shed. In this myth, his spirit of revelry and fertility can be seen as an underlying current, influencing the atmosphere of the festival that became the catalyst for the abduction.

-

Romulus: The legendary founder and first king of Rome, Romulus embodies the Roman ideals of leadership, determination, and pragmatism. Having founded his city on the Palatine Hill, he faced the existential crisis of a city populated almost entirely by men – a collection of exiles, adventurers, and shepherds. His actions, though controversial from a modern perspective, were seen by ancient Romans as necessary and decisive for the survival of their nascent state. He symbolizes the ruthless efficiency and foresight required for nation-building.

-

The Sabine Women: Hailing from the neighboring Sabine tribes, these women represent the essential element for Rome’s survival – the means to continue its lineage. Initially victims of a calculated abduction, they transcend this role to become powerful symbols of integration, peace, and the transformative power of adaptation. Their initial fear and sorrow give way to a profound loyalty to their new families and, ultimately, to their new city.

-

The Sabines (Titus Tatius): The Sabines were a proud, warlike people, symbolizing the established order and the aggrieved party. Led by their king, Titus Tatius, they represent the righteous anger and honor-bound response to a grave affront. Their initial pursuit of vengeance ultimately leads to an unexpected union, demonstrating the ability of societies to forge new bonds from conflict.

4. Main Story / Narrative Retelling

The tale begins in the rugged hills of Latium, where Romulus, having established his city of Rome, faced a dire predicament. His fledgling settlement, a haven for men seeking new lives, lacked the one element crucial for its longevity: women. Without wives, there would be no children, and without children, Rome was destined to wither and die, its grand vision reduced to a fleeting memory.

Romulus, a shrewd and determined leader, initially sought to address this issue through diplomacy. He dispatched envoys to neighboring tribes, including the proud Sabines, proposing intermarriage and alliances. However, his overtures were met with scorn and rejection. The established communities viewed Rome as a crude collection of outcasts and bandits, unworthy of their daughters. Their disdain only fueled Romulus’s resolve.

With peaceful means exhausted, Romulus devised a audacious plan. He announced a grand festival, the Consualia, to be held in honor of Consus, an ancient Roman deity of counsel and harvests. He spread word far and wide, inviting all neighboring peoples, including the Sabines, to partake in the festivities, promising games, feasting, and entertainment. This invitation, extended under the guise of religious devotion and hospitality, was a strategic lure.

As the day of the Consualia arrived, the fields outside Rome thronged with eager spectators. The Sabines, renowned for their austere lifestyle, arrived in significant numbers, bringing their wives and daughters, drawn by curiosity and the spirit of shared celebration. The air buzzed with excitement, the festive mood, fueled by wine and revelry, creating an atmosphere ripe for the unexpected. While not explicitly dedicated to Bacchus, the sheer scale of the feasting and the intoxicating spirit of the occasion certainly fell within the god of wine’s domain, subtly disarming the visitors and setting the stage for the dramatic turn of events.

At a prearranged signal from Romulus – a dramatic gesture, perhaps the removal of his cloak – the Roman men, who had been mingling innocently among the crowds, sprang into action. With a sudden surge, they seized the unmarried Sabine women, carrying them off into the heart of the Roman settlement. Chaos erupted. The Sabine men, outraged and caught off guard, were unable to prevent the mass abduction. They returned to their homes, seething with a righteous fury, vowing vengeance.

The abducted women, initially terrified and weeping, found themselves in an alien city, forced into marriages with their captors. Romulus, understanding their plight, addressed them directly. He assured them that they would be treated with honor, become Roman wives, and mothers of the next generation of Romans, promising them full rights and status within their new society. He appealed to their maternal instincts, emphasizing the necessity of their role in the founding of a great nation. Slowly, painstakingly, some of the women began to adapt, their initial fear giving way to resignation, and for some, even affection, as they bore children and built lives with their Roman husbands.

Meanwhile, the Sabines, led by their King Titus Tatius, meticulously prepared for war. Their honor had been gravely insulted, their daughters stolen. They marched on Rome, determined to reclaim their women and exact retribution. The ensuing conflict was fierce, a brutal clash between two determined peoples. The Romans, fighting for their nascent city and their newly acquired wives, met the Sabines with equal ferocity.

The climax of the war arrived during a pivotal battle. As the two armies clashed, swords ringing and shields clashing, an extraordinary sight unfolded. The Sabine women, now Roman wives and mothers, with their children in their arms, rushed onto the battlefield. With disheveled hair and tear-streaked faces, they placed themselves directly between the warring factions – between their fathers and brothers on one side, and their Roman husbands on the other.

Their pleas were heart-wrenching. They implored both sides to cease the bloodshed, arguing that whichever side won, they would lose – either their fathers or their husbands, their brothers or the fathers of their children. "We are the cause of this war, and we would rather die than see our loved ones perish!" they cried. Their intervention, an act of immense courage and desperation, moved both armies. The sight of their daughters and sisters, now mothers themselves, shamed the Sabines, and the pleas of their wives softened the hearts of the Romans.

The fighting ceased. A truce was called, followed by negotiations. The conflict, born of abduction, ended in an unprecedented act of reconciliation. A peace treaty was struck, leading to a remarkable union: the Romans and Sabines agreed to merge into a single nation. Titus Tatius became co-ruler with Romulus, and the two peoples were integrated, sharing citizenship and customs. The Sabine women, once symbols of division, became the very fabric of this new, unified society.

5. Symbolism and Meaning

This myth is rich with symbolism, offering insights into ancient Roman values and their understanding of their own origins:

- Founding of Rome: The story serves as a foundational myth, explaining how Rome overcame an existential threat to secure its future. It legitimizes the city’s growth and its ability to absorb and integrate other peoples.

- Resourcefulness and Determination: Romulus’s audacious plan, though morally questionable by modern standards, symbolizes the Roman spirit of pragmatism and relentless pursuit of their goals.

- The Role of Women: The Sabine Women, initially passive victims, evolve into active agents of peace and unity. Their intervention highlights their crucial role not just in bearing children, but as mediators and shapers of social cohesion. It reflects the Roman emphasis on the family unit as the cornerstone of society.

- Integration and Assimilation: The ultimate union of Romans and Sabines illustrates Rome’s historical capacity to absorb conquered or neighboring peoples, integrating them into its political and social structure.

- Bacchic Influence (Implicit): The spirit of revelry and the underlying theme of fertility, essential for Rome’s continuation, can be symbolically linked to Bacchus. His domain of intoxicating freedom and raw life force provides a context for the passionate, albeit violent, act of procreation and nation-building. The disruption of societal norms for a higher purpose (survival of Rome) resonates with the boundary-breaking nature attributed to Bacchus.

6. Modern Perspective

Today, the myth of the Sabine Women continues to resonate, though its interpretation has evolved significantly. In literature, art, and cultural studies, it is often examined through the lens of power dynamics, gender roles, and the ethical ambiguities of nation-building.

Artists like Jacques-Louis David famously depicted "The Intervention of the Sabine Women," focusing on the dramatic plea for peace. Historians analyze the story as a mythological explanation for Roman expansion and the assimilation of other Italic tribes. Modern interpretations critically engage with the term "rape" (Latin: raptio), acknowledging that while it meant "abduction" or "seizure" rather than sexual assault in the ancient context, it still represents a profound violation of autonomy and a forceful act against women.

The myth serves as a stark reminder of the often-violent origins of ancient societies and prompts discussions about consent, the role of women in conflict, and the ways in which historical narratives are constructed to justify foundational events. It remains a compelling story for its dramatic narrative, its exploration of human resilience, and its enduring questions about justice and survival.

7. Conclusion

The tale of Bacchus and the War of the Sabine Women is a powerful testament to the imaginative capacity of ancient cultures, a story that shaped the identity of a civilization. It is a traditional narrative, a myth from a bygone era, and is not to be understood as a factual account or a basis for belief. As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah is the true Creator and Sustainer of all that exists, and these ancient stories are human constructs, products of their time and culture.

This myth, like countless others, forms an invaluable part of our global cultural heritage, offering a window into the fears, aspirations, and values of ancient peoples. It underscores the enduring human tradition of storytelling – a way to make sense of the world, to transmit values, and to ponder the profound questions of existence, even if through the lens of fantastic and legendary narratives. The legacy of such myths lies not in their literal truth, but in their capacity to spark imagination, inspire critical thought, and connect us to the vast, diverse tapestry of human experience across millennia.