Introduction:

This tale comes from the rich tapestry of folklore woven by the Tagalog people of the Philippines, specifically those communities nestled around the majestic, cone-shaped volcano known as Mayon. This is a story of creation, not as we understand it with the singular, divine hand of Allah, but as imagined by the ancestors who lived in the shadow of the mountain, a time long before the arrival of Islam. This is a traditional story, a product of a culture’s deep connection to the land and their attempt to understand the forces of nature that shaped their lives. It is a story to be examined, understood, and appreciated for its cultural significance, not a belief to be held as truth.

Origins and Cultural Background:

The era in which this myth took root was one defined by the rhythm of the seasons, the bounty of the land, and the unpredictable power of nature. Before the Spanish colonial era, the Tagalog people lived in small, independent barangays (villages), each ruled by a datu (chief). Life revolved around agriculture, fishing, and trade. The environment was both a provider and a threat. Lush rice paddies, teeming rivers, and fertile forests offered sustenance, but typhoons, floods, and the ever-present threat of volcanic eruptions from Mayon shaped their worldview.

The people of that time saw the world as a complex interplay of spirits, both benevolent and malevolent. They believed in anitos, the spirits of ancestors, and other nature spirits that inhabited the trees, rivers, and mountains. These spirits, they believed, influenced every aspect of life, from the success of a harvest to the health of a child. Mayon Volcano, with its dramatic eruptions, was not just a geological feature but a living entity, a powerful being whose moods and actions directly impacted the lives of the people. Their understanding of the world was animistic, meaning they attributed a soul or spirit to all living and non-living things, and deeply connected to the natural world.

Character / Creature Description:

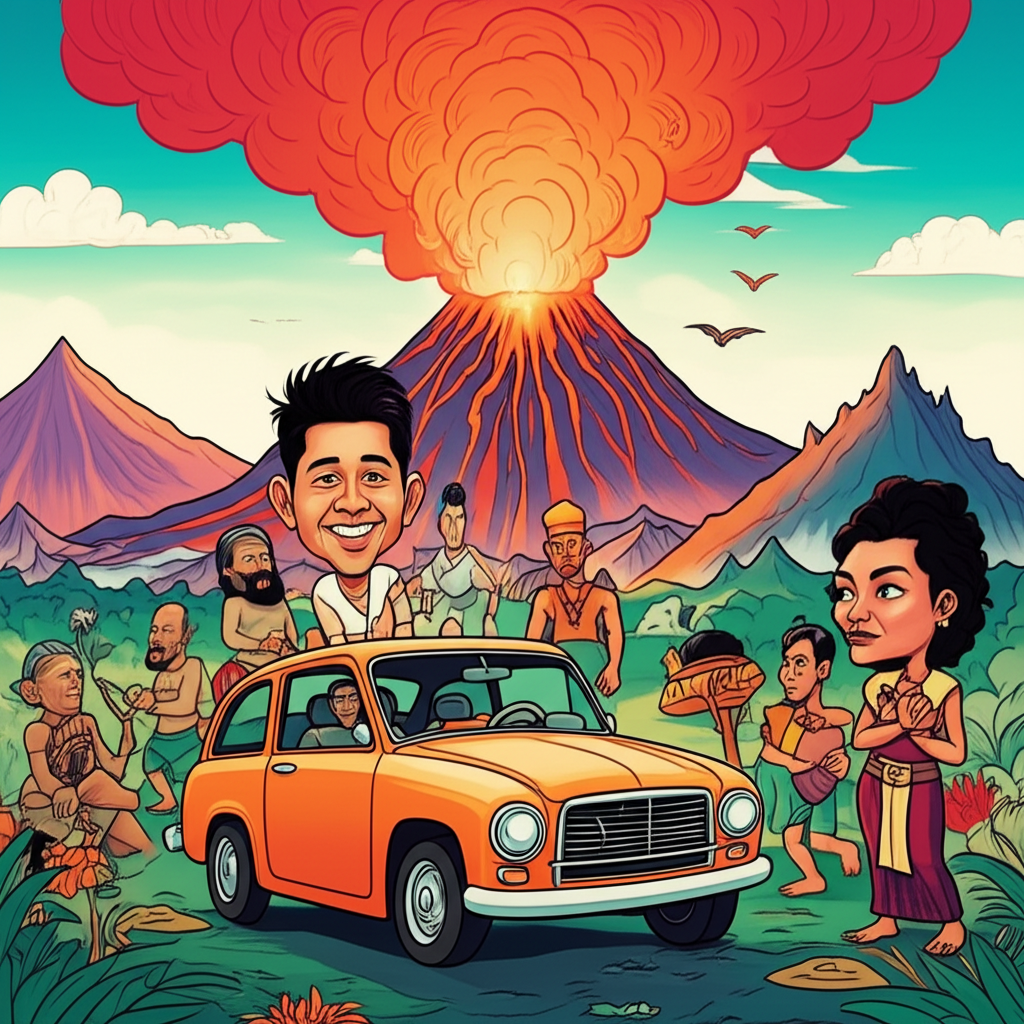

The central figure in this creation story is the volcano itself, Mayon, but not as a mere mountain. It is personified as a beautiful maiden, a princess of unparalleled loveliness named Daragang Magayon, meaning "Beautiful Maiden." She is often depicted with long, flowing hair that mimics the smoke plumes and a gentle, graceful demeanor that reflects the mountain’s apparent serenity.

The symbolic attributes of Daragang Magayon are numerous. She represents the fertility of the land, the source of life and sustenance. Her beauty is symbolic of the allure and power of nature. She is also a figure of tragedy, her fate a cautionary tale about love, jealousy, and the destructive forces that can arise from unchecked emotions. The volcano, when it erupts, is seen as the manifestation of her grief and anger, a physical embodiment of her suffering and the consequences of the events that led to her demise. The perfect cone of the volcano is her resting place, a lasting monument to her beauty and the events that shaped the landscape.

Main Story / Narrative Retelling:

The story begins with Daragang Magayon, the most beautiful maiden in the land, residing in a lush valley. She was sought after by many suitors, but her heart remained untouched. Among those vying for her affection was Ulap, a valiant warrior, known for his bravery and kindness, whose name means "Cloud." He came from a rival tribe, and their love was forbidden.

One day, while Daragang Magayon was bathing in a river, a hunter and a chieftain named Pagtuga, known for his cruelty and lust, saw her. He was instantly captivated. When Daragang Magayon refused his advances, Pagtuga, consumed by rage and jealousy, kidnapped her.

Ulap, upon hearing of Daragang Magayon’s capture, gathered his warriors and waged war against Pagtuga to free her. A fierce battle ensued. Ulap fought bravely, but in the chaos, an arrow, shot by Pagtuga’s men, pierced Daragang Magayon. Ulap, seeing his beloved fall, rushed to her side, only to be struck down himself.

As the lovers lay dying, the earth trembled. The ground split open, and the volcano, which had been dormant for centuries, began to erupt with fury. Rivers of molten rock poured down the slopes, burying the lovers and their enemies. The people, witnessing the devastation, believed that the volcano was Daragang Magayon, weeping in rage and sorrow for the loss of her love.

When the eruption subsided, a perfect cone-shaped mountain remained, where the lovers were said to be buried. The villagers named it Mayon, in honor of Daragang Magayon. They believed that the clouds that often gather around the summit are Ulap embracing his beloved.

Symbolism and Meaning:

The story of Daragang Magayon and the eruption of Mayon Volcano is rich in symbolism. The volcano itself represents the power and unpredictability of nature. The eruption signifies the destructive consequences of unchecked emotions, specifically jealousy, lust, and anger. The tragic fate of the lovers highlights the destructive nature of conflict and the sacrifices made for love.

The story also speaks to the importance of community and the interconnectedness of all things. The loss of Daragang Magayon and Ulap impacts the entire region, and the eruption serves as a constant reminder of the fragility of life. It’s a story about consequences, about the delicate balance between beauty and destruction, and the enduring power of love even in the face of death. It also gives an explanation for the physical shape of the volcano, a visual manifestation of a tragic love story.

Modern Perspective:

Today, the story of Daragang Magayon is a cornerstone of Tagalog cultural heritage. It continues to be retold in countless forms. It has inspired numerous works of literature, poetry, and music. The legend is a frequent subject in movies and television dramas. It’s often used as a backdrop for romantic tales, where the beauty and the power of the volcano are seen as an embodiment of the story’s emotional intensity.

The story is also a popular theme in art, with depictions of Daragang Magayon and the eruption adorning paintings, sculptures, and other forms of visual art. The volcano itself has become a major tourist attraction, with the legend of Daragang Magayon serving as a powerful marketing tool. In cultural studies, the myth is analyzed for its historical and social significance, exploring how it reflects the values, beliefs, and fears of the ancient Tagalog people.

Conclusion:

This narrative of the creation of Mayon, born from the imaginations of the Tagalog people, offers a glimpse into a world shaped by nature and infused with the spirits of ancestors. It is a story of beauty, tragedy, and the enduring power of love, but it is not a story to be taken as religious truth.

As Muslims, we believe in the absolute oneness of Allah (SWT), the one and only Creator and Sustainer of all existence. Our understanding of creation is guided by the verses of the Quran and the teachings of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). While we acknowledge the rich cultural heritage of the Tagalog people and appreciate the beauty and complexity of their storytelling tradition, our faith rests solely on the divine word of Allah.

May this tale serve as a reminder of the power of imagination and the importance of preserving cultural heritage. It is a story that allows us to appreciate the creativity and ingenuity of our ancestors, even as we maintain our unwavering belief in the one true God. Let us reflect on the power of storytelling to connect us to the past, enrich our present, and inspire our future.