From the mists of time, where ancient forests whispered secrets to the wind and the very earth seemed alive with unseen forces, emerges a captivating narrative from the Celtic world. These tales, woven by the peoples of ancient Europe – those who dwelled in lands of rolling hills, dense woodlands, and rugged coastlines – offer a glimpse into their worldview. The story of Cernunnos and the Eternal Sea is one such traditional narrative, a tapestry of imagination and a reflection of how our ancestors sought to understand the world around them. It is crucial to remember that these are ancient stories, born from human creativity and the desire to explain the mysteries of existence, not literal accounts of divine beings.

The cultural era in which these myths took root was one of deep connection to nature. The Celts, a collection of tribes spread across much of Europe from the 8th century BCE to the 1st century CE, lived in close proximity to the natural world. Their lives were dictated by the seasons, the fertility of the land, and the untamed power of the elements. They perceived the world as imbued with spirit; every tree, river, and mountain could possess a sacred essence. Their understanding was not based on abstract scientific principles, but on observation, intuition, and a profound respect for the cycles of life and death. In such a context, figures embodying the wildness and generative power of nature would naturally arise in their storytelling.

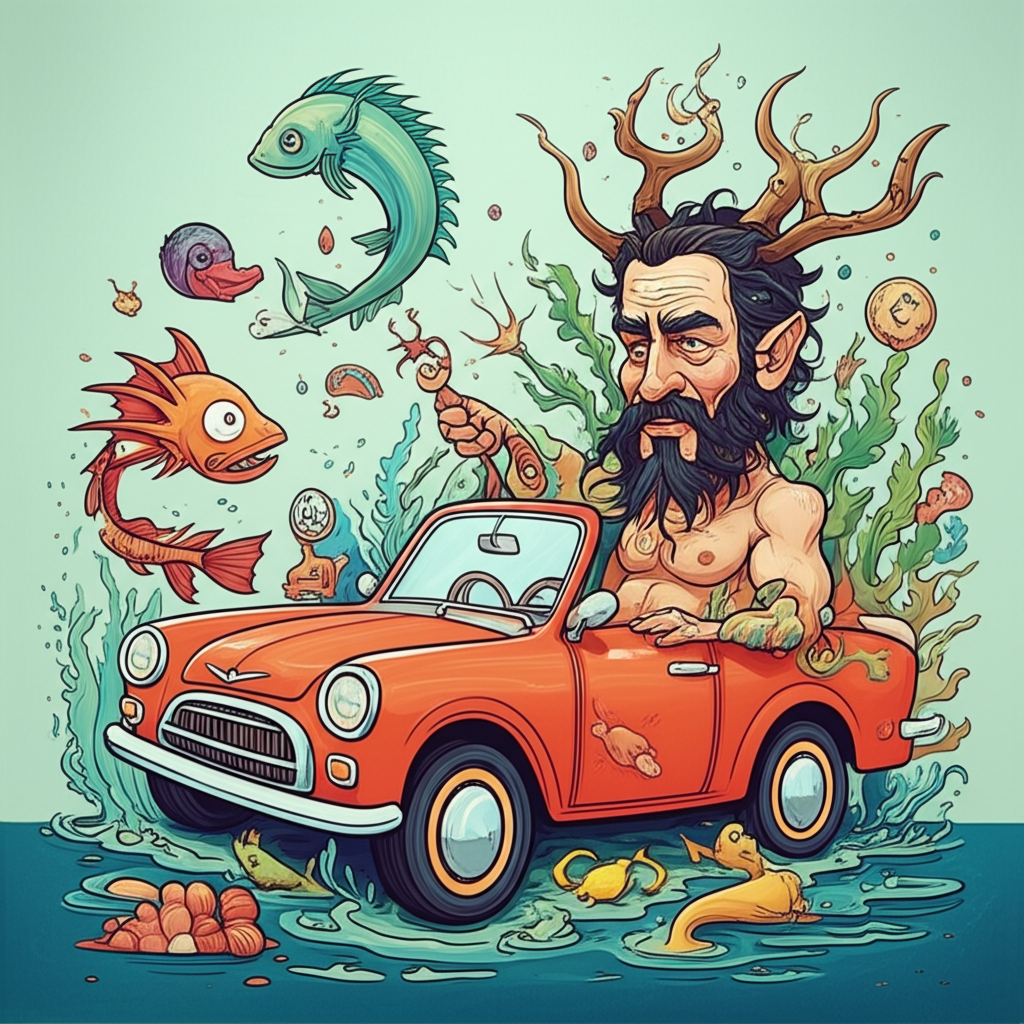

Central to this narrative is the figure of Cernunnos. He is often depicted as a powerful, horned deity, a primal force associated with the wilderness, fertility, and the cyclical nature of life. His form is typically that of a man with the antlers of a stag, sometimes adorned with torcs – heavy neck rings symbolizing wealth and status, but also potentially representing the cyclical nature of time or the connection between the earthly and the divine. He might be shown seated, a posture of contemplation or authority, surrounded by animals – stags, wolves, boars, serpents – underscoring his dominion over the wild kingdom. These symbolic attributes speak to the ancient Celts’ reverence for the strength and resilience of the stag, the ferocity of the wolf, and the potent, regenerative force of the serpent. Cernunnos, in this context, represents the untamed spirit of the wild, the abundance of the forest, and the ongoing dance of creation and decay.

The chronicle tells of Cernunnos, the Lord of the Wild, who dwelled at the heart of an ancient, verdant forest, a place where sunlight dappled through leaves that had witnessed millennia. His domain was one of perpetual growth and vibrant life, a testament to his nurturing power. Yet, beyond the whispering trees, where the land met the sky in an unending horizon, lay the Eternal Sea. This was not merely water; it was the primal source, the vast, unfathomable expanse from which all things emerged and to which all things eventually returned. The Sea was a realm of immense power, its tides a constant reminder of change and the relentless march of time.

It is said that Cernunnos, while overseeing the flourishing life of his forest, felt a profound connection to the rhythm of the Eternal Sea. He understood that the life he fostered in the woods was intrinsically linked to the oceanic currents, to the rain that fell from the sky and was born of the Sea’s vastness. The Sea, in turn, was a mirror of the forest’s cycles – its storms reflecting the fury of the wild, its calm waters the deep stillness of ancient groves.

One ancient tale recounts a time of imbalance. The Sea, in its infinite depth, grew restless. Its waves churned with an unusual ferocity, threatening to engulf the lands, to erase the delicate balance that Cernunnos had so carefully cultivated. The animals of the forest grew fearful, their usual boisterous calls replaced by hushed anxieties. The leaves themselves seemed to tremble.

Cernunnos, sensing this disharmony, rose from his seated throne. His antlers, as broad and intricate as the branches of the oldest oaks, caught the dappled light. He did not confront the Sea with aggression, for he understood that such a force could not be conquered by brute strength. Instead, he walked to the very edge of his domain, where the last of the ancient trees bowed to the encroaching salt spray.

He stood at the precipice, a figure of quiet strength, and offered a silent communion with the churning waters. He projected the essence of the forest’s resilience, its capacity for renewal, its deep-rooted peace. He showed the Sea the beauty of the life it nourished, the vibrant hues of the forest floor, the soaring flight of birds, the silent strength of ancient roots. He conveyed that true power lay not in overwhelming destruction, but in the continuous, cyclical embrace of creation and dissolution.

As Cernunnos communed with the Eternal Sea, the tempest began to subside. The raging waves softened, their roars diminishing to a rhythmic ebb and flow. The sky, once turbulent, cleared, revealing a celestial canopy. The forest breathed a collective sigh of relief, its vibrant colors returning with renewed intensity. Cernunnos had, through his profound understanding of the interconnectedness of all things, helped to restore the ancient balance. This story, as told by ancient peoples, was a way of acknowledging the immense power of nature and the delicate equilibrium that sustained life.

The symbolism within this chronicle is rich and multifaceted. Cernunnos, with his connection to both the forest and the creatures within it, represents the primal forces of nature – fertility, abundance, the cycle of life and death, and the untamed wild. His antlers can be seen as a symbol of his connection to the sky and the heavens, while his animal companions represent the diverse manifestations of life under his dominion. The Eternal Sea embodies the vast, primordial forces of the cosmos, the source of all creation, and the ultimate destination of all existence. Its tides symbolize the constant flux of the universe, the inevitability of change, and the immense, often unpredictable, power of the natural world. The story suggests a profound interconnectedness between seemingly disparate realms, a belief that the health of the land was inextricably linked to the power of the sea and the heavens. It also speaks to a form of cosmic balance, where understanding and respect, rather than outright dominion, were key to maintaining harmony.

In the modern world, these ancient myths continue to resonate. Cernunnos, as a figure of wild power and connection to nature, has found a place in contemporary literature, fantasy gaming, and various forms of neo-paganism, where he is interpreted in diverse ways as a symbol of the earth’s vitality and the enduring spirit of the wild. His image and story are explored in academic studies of Celtic mythology, offering insights into the spiritual and philosophical landscape of ancient European societies. Scholars analyze these narratives for their archetypal themes of creation, destruction, and renewal, and their reflection of humanity’s long-standing relationship with the natural world.

It is important to reiterate that the chronicle of Cernunnos and the Eternal Sea is a traditional story, a product of human imagination from a bygone era. It offers a fascinating window into the beliefs and worldview of ancient peoples. As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah (God) is the true Creator and Sustainer of the universe, the ultimate source of all power and existence. These ancient narratives, while culturally significant and rich in symbolism, do not alter this fundamental truth.

Ultimately, these stories serve as a testament to the enduring power of human storytelling and our innate desire to understand our place within the vast tapestry of existence. They remind us of the deep connection our ancestors felt to the natural world and the imaginative ways they sought to explain its mysteries. The chronicle of Cernunnos and the Eternal Sea, like countless other myths and legends, is a precious thread in the rich tapestry of our collective cultural heritage, a reminder of the boundless capacity of the human mind to create, to question, and to wonder.