Ganesha and the Journey of Mahabharata Episodes

1. Introduction:

The story of how the Mahabharata, one of the most extensive and influential epics in Indian tradition, came to be written is intertwined with the figure of Ganesha, the elephant-headed deity. This narrative, originating from the rich tapestry of Hindu mythology, is a traditional story passed down through generations, a testament to the power of oral tradition and the human desire to understand the world through allegory and symbolic representation. This tale, recounted in various Puranas (ancient Hindu texts), speaks not of divine intervention in a literal sense, but of the enduring themes of knowledge, dedication, and the importance of preserving cultural heritage.

2. Origins and Cultural Background:

The era in which this myth likely gained prominence was the classical period of India, a time marked by significant advancements in philosophy, literature, and the arts (roughly 3rd century BCE to 5th century CE). Society was structured around a complex system of social hierarchies, and religious beliefs permeated every aspect of life. People of that time viewed the world as a stage for divine play (lila), where gods and goddesses interacted with humans, influencing their destinies and serving as archetypes for human behavior. The concepts of dharma (righteous conduct), karma (action and consequence), and moksha (liberation) were central to their understanding of existence. The Mahabharata itself reflects this worldview, exploring these themes through its intricate narrative and multifaceted characters. The oral tradition was a primary method of transmitting knowledge and cultural values, making storytelling a crucial art form.

3. Character Description:

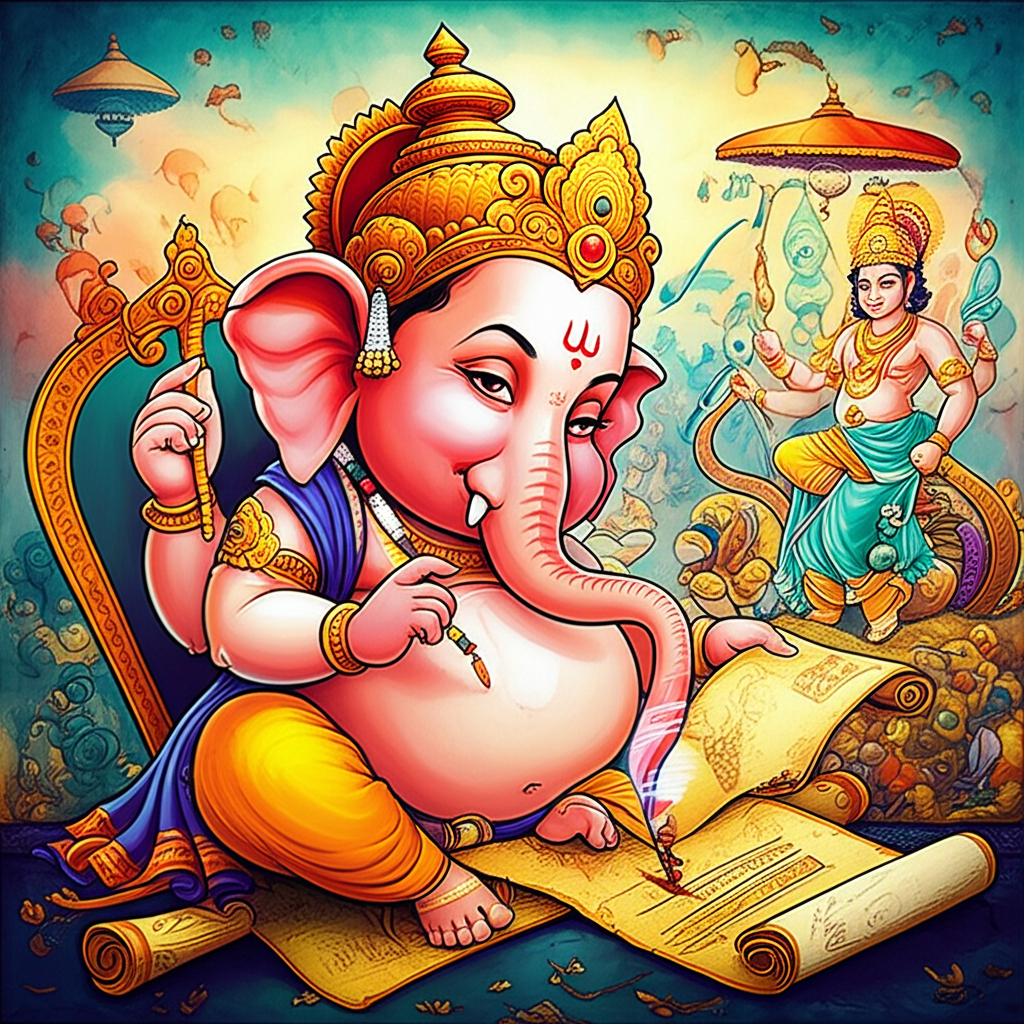

Ganesha, in this narrative, is presented not as a literal deity, but as a figure imbued with symbolic attributes. He is depicted with an elephant’s head, a large belly, and often with one tusk broken.

- Elephant Head: This is often interpreted as representing wisdom, intellect, and the ability to overcome obstacles. The large head signifies great thinking capacity.

- Large Belly: This symbolizes the ability to digest and accept all experiences, both good and bad, demonstrating a capacity for understanding and tolerance.

- Broken Tusk: This represents sacrifice and the willingness to give up something for a greater purpose. In some versions of the story, Ganesha breaks his tusk to use it as a pen to write the Mahabharata.

- Mouse (his Vahana): The mouse, Ganesha’s mount, represents humility and the ability to navigate through complexities.

These attributes, understood symbolically, offered a framework for understanding desirable qualities such as wisdom, resilience, and dedication.

4. Main Story / Narrative Retelling:

The sage Vyasa, having conceived the epic Mahabharata in his mind, realized he needed a scribe capable of keeping pace with his rapid recitation. The Mahabharata was to be a vast and complex narrative encompassing history, philosophy, and moral teachings, far too extensive for ordinary human scribes.

Vyasa approached Brahma, the creator god, for guidance. Brahma advised him to seek the assistance of Ganesha, known for his intellect and ability to overcome obstacles.

Vyasa prayed to Ganesha, requesting him to be his scribe. Ganesha, understanding the magnitude of the task, agreed, but with a condition: Vyasa must recite the poem without pause. Ganesha would only write if Vyasa never hesitated or faltered.

Vyasa, in turn, proposed a condition of his own: Ganesha must understand every word and verse before writing it down. This condition was crucial. Vyasa knew that Ganesha’s intellect was vast, but he wanted to ensure that the essence of the epic was fully grasped and not merely transcribed mechanically.

Thus began the monumental task. Vyasa would recite the verses, often interweaving complex philosophical concepts and intricate narratives within the main storyline. Ganesha, with his focus and intelligence, would carefully consider each verse before committing it to writing. When Vyasa needed a moment to formulate a particularly difficult passage, he would insert verses filled with complex metaphors and philosophical nuances, giving Ganesha time to ponder while maintaining the flow of recitation.

It is said that Ganesha broke his tusk during the writing process, using it as a pen to continue writing without interruption. This act of self-sacrifice underscored his commitment to the project and the importance of preserving the epic.

The process continued for many years, resulting in the Mahabharata, an epic of unparalleled scope and depth.

5. Symbolism and Meaning:

This story, viewed symbolically, offers insights into the values held by ancient people. The tale may have represented:

- The Importance of Knowledge: The Mahabharata is a repository of knowledge, and the story emphasizes the value placed on learning and understanding.

- The Power of Dedication: Both Vyasa and Ganesha demonstrate unwavering dedication to their respective roles, highlighting the importance of commitment in achieving a goal.

- The Balance of Intellect and Understanding: The conditions set by both Vyasa and Ganesha symbolize the need for both intellectual prowess (Ganesha’s ability to write rapidly) and deep understanding (Ganesha’s need to comprehend each verse).

- The Role of the Storyteller and the Listener: The dynamic between Vyasa and Ganesha mirrors the relationship between the storyteller and the listener, emphasizing the responsibility of both parties in preserving and transmitting cultural knowledge.

- Sacrifice for a Greater Good: Ganesha breaking his tusk is symbolic of sacrificing something of value for the sake of a larger purpose.

6. Modern Perspective:

The story of Ganesha and the Mahabharata continues to resonate in modern times. It is often referenced in literature, movies, and games as a symbol of wisdom, dedication, and the power of storytelling. Cultural studies scholars analyze the narrative for its insights into ancient Indian society, its values, and its understanding of the world. The image of Ganesha, particularly in his role as the scribe of the Mahabharata, is used to promote literacy and education. The story is used as a source of inspiration for artists, writers, and filmmakers, demonstrating the enduring appeal of ancient myths.

7. Conclusion:

The tale of Ganesha and the writing of the Mahabharata remains a captivating story. It’s a valuable piece of cultural heritage, offering a glimpse into the worldview and values of ancient people. As Muslims, we understand that only Allah is the Creator and Sustainer of the universe, and we do not assign divine powers to any other being. However, we can still appreciate the cultural richness and imaginative power of this story, recognizing it as a product of human creativity and a testament to the enduring power of storytelling traditions. This story, like many others from different cultures, reminds us of the shared human desire to understand the world, to grapple with complex moral questions, and to preserve our collective history through the art of narrative.