Disclaimer: The following article explores a story from ancient mythology for cultural, historical, and educational purposes. It is a work of folklore and is not intended to be regarded as a factual or religious account. It does not represent any form of belief, worship, or practice.

Introduction

From the sun-drenched shores and rocky isles of the Aegean Sea, the ancient Greeks wove a rich tapestry of myths to explain their world. These were not just simple tales, but complex narratives that explored the depths of human nature, the chaos of the cosmos, and the intersection of mortal lives with powerful, often capricious, divine forces. One of the most pivotal of these stories is the Judgment of Paris. This traditional legend, passed down through epic poems and oral traditions, serves as the critical spark that ignites the flames of the most famous conflict in Western mythology: the Trojan War. It is a story not of grand battles, but of a single, fateful choice—a choice that would ultimately send a generation of heroes down the path to their fated end, and for some, to the idyllic afterlife of Elysium.

Origins and Cultural Background

This myth emerged from the cultural environment of Archaic and Classical Greece (roughly 8th to 4th centuries BCE). This was a society organized into fiercely independent city-states, a world that gave birth to democracy, philosophy, and theater. The ancient Greeks viewed their world as a stage where human drama unfolded under the watchful eyes of the Olympian gods. These deities were not distant, abstract beings; they were anthropomorphic, possessing all the virtues and, more importantly, the flaws of humanity: pride, jealousy, vanity, and a tendency to meddle in mortal affairs.

Myths like the Judgment of Paris were shared in poetic recitations, painted on pottery, and sculpted in stone. They were a part of the cultural fabric, providing a shared framework for understanding morality, destiny, and the devastating consequences of human fallibility. The story itself is a key prequel to the events of Homer’s The Iliad, setting the divine and mortal motivations for the decade-long siege of Troy.

The Figures of the Fateful Choice

To understand the story, one must first understand the symbolic nature of its key participants:

- Eris: The personification of Strife or Discord. In the Greek worldview, she was not necessarily evil, but a fundamental force of chaos. Her presence represents the idea that conflict can arise from the smallest, most unexpected slight.

- Hera: The queen of the gods and wife of Zeus. She symbolized power, empire, and the sanctity of marriage. Her domain was order, royalty, and dominion over vast lands.

- Athena: The goddess of wisdom, strategic warfare, and crafts. Born fully formed from the head of Zeus, she represented intellect, reason, and the glory won through skill and tactical prowess rather than brute force.

- Aphrodite: The goddess of love, beauty, and desire. Her influence was that of overwhelming passion and physical attraction, a powerful and often uncontrollable force in both mortal and divine lives.

- Paris: A prince of Troy, who, due to a prophecy that he would bring about the city’s downfall, was left to die on Mount Ida as an infant but was rescued and raised by a shepherd. He came to represent the flawed nature of human judgment, easily swayed by personal desire over greater responsibilities.

The Narrative Retelling: A Choice that Shook the Heavens

The saga begins not with war, but with a celebration. On Mount Olympus, a grand wedding was held for the sea-nymph Thetis and the mortal king Peleus. All the gods and goddesses were invited to the joyous occasion, with one pointed exception: Eris, the goddess of Discord, for her presence was known to sour any gathering.

Slighted and angered by the exclusion, Eris devised a simple yet devastating plan for revenge. She appeared at the edge of the festivities, unseen, and rolled a solid gold apple among the guests. Etched upon its gleaming surface were the words Te Kallisti—"To the Fairest."

Immediately, the festive atmosphere curdled. Three of the most powerful goddesses each laid claim to the prize: Hera, the regal queen; Athena, the wise warrior; and Aphrodite, the embodiment of beauty. Their bickering threatened to tear the divine court apart. Zeus, the king of the gods, found himself in an impossible position. To choose one would be to earn the eternal enmity of the other two. With shrewd political maneuvering, he abdicated responsibility, declaring that a mortal must decide—one known for his impartiality.

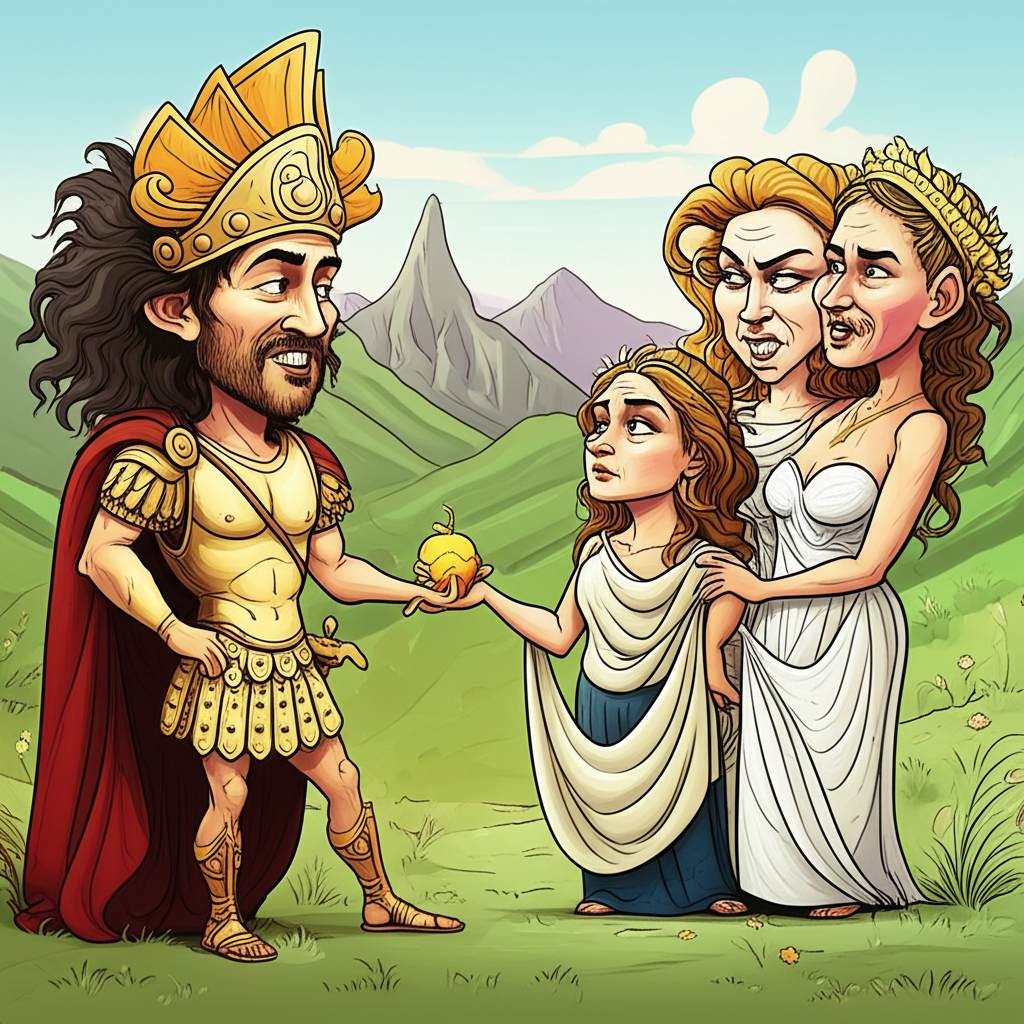

His choice fell upon Paris, the young prince of Troy living as a humble shepherd on the slopes of Mount Ida, unaware of his royal lineage. The messenger god Hermes was dispatched to guide the three goddesses to the mortal judge. Paris, tending his flock, was stunned as the shimmering figures materialized before him. Hermes presented the golden apple and explained the task: he was to award it to the most beautiful among them.

Terrified but left with no alternative, Paris prepared to judge. But the goddesses were not content to rely on their appearance alone. They resorted to bribery, each stepping forward to offer a prize worthy of a god.

First came Hera, her voice resonant with authority. "Choose me, Paris," she declared, "and I will make you king of all Europe and Asia. You will have power beyond any mortal’s dream, with empires at your command." The offer was staggering: ultimate political dominion.

Next, Athena stepped forward, her gray eyes sharp and intelligent. "Power is fleeting, mortal," she advised. "Choose me, and I will grant you wisdom and skill in war. You will lead the Trojan armies to victory in every battle. Your name will be remembered for glory and strategic genius." The offer was for immortal fame through wisdom and military might.

Finally, Aphrodite approached, her presence exuding an irresistible charm. She did not promise power or glory. Instead, she smiled and spoke in a soft, persuasive whisper. "What are empires or battles compared to love, Paris? Award me the apple, and I will give you the most beautiful mortal woman in the world to be your wife: Helen of Sparta."

For Paris, a young man driven by passion rather than ambition, the choice was clear. The allure of Helen, a woman famed throughout the lands for her unparalleled beauty, was a temptation he could not resist. He handed the golden apple to Aphrodite, sealing his fate and the fate of his city. In that moment, he secured Aphrodite as his divine patron but earned the deep and unforgiving hatred of both Hera and Athena, two of the most formidable powers on Olympus. Their wrath would soon be directed at Paris and all of Troy.

Symbolism and Meaning

To the ancient Greeks, the Judgment of Paris was a profound cautionary tale. It symbolized the catastrophic consequences that can spring from a single, selfish decision. Paris’s choice was not just about which goddess was the "fairest," but an allegorical selection between three ways of life: political power (Hera), wisdom and glory (Athena), and romantic passion (Aphrodite). His selection of passion over duty and reason was depicted as a critical moral failure, leading directly to a devastating war that would destroy his family, his city, and an entire generation of heroes. The story served as a lesson on the dangers of vanity, the corrupting influence of temptation, and the idea that human actions have far-reaching, often unforeseen, consequences. The "apple of discord" became an enduring symbol for any small issue that could trigger a much larger conflict.

Modern Perspective

The Judgment of Paris has resonated through centuries of Western culture. It has been a favorite subject for artists, most famously captured in the lavish paintings of Peter Paul Rubens and Lucas Cranach the Elder. In literature, it is the foundational event for countless retellings of the Trojan War, from ancient epics to modern novels. The story’s central dilemma—the choice between power, wisdom, and love—remains a potent metaphor in philosophical and psychological discussions. The phrase "apple of discord" has entered the modern lexicon, used to describe the root cause of an argument or dispute. It continues to be studied as a classic example of how mythology encapsulates timeless human truths about choice, consequence, and conflict.

Conclusion

The Judgment of Paris is more than just a quaint story about bickering goddesses; it is a powerful piece of cultural heritage that offers a window into the ancient Greek psyche. It is a product of human imagination, a narrative crafted to explore complex themes of fate, free will, and the origins of conflict. As a mythological account, it stands as a testament to the storytelling traditions of a civilization that sought to understand the world through epic, symbolic narratives.

As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah is the true Creator and Sustainer, the sole source of all power and wisdom. These ancient myths are viewed not as theological truths, but as historical and literary artifacts. They remind us of the enduring human impulse to tell stories, to make sense of our place in the universe, and to caution future generations through the lessons of the past. The echo of Paris’s choice reminds us that stories, whether factual or imagined, hold a unique power to shape our understanding of human nature and the world we inhabit.