The mists of antiquity, stretching back to the sun-drenched landscapes of ancient Rome, whisper tales of gods, goddesses, and the rituals that marked their lives. Among these enduring narratives is the story of Diana and the Trial of Saturnalia, a legend that offers a glimpse into the worldview and customs of a civilization long past. It is crucial to understand that this is a traditional story, a product of ancient imagination and cultural expression, not a factual account or a divine decree.

The era in which such myths flourished was one of profound connection to the natural world and a deep-seated belief in the forces that governed it. Ancient Romans, much like many early societies, sought to understand the cycles of seasons, the bounty of the harvest, and the mysteries of life and death through the lens of mythology. Their world was populated by anthropomorphic deities, each embodying aspects of nature, human endeavor, and cosmic order. Festivals, often tied to agricultural cycles and celestial events, were integral to their social fabric, serving as communal expressions of devotion, celebration, and a desire to appease or honor these powerful, unseen forces. Saturnalia, the festival from which this story draws its name, was a particularly significant and joyous occasion, a period of revelry and inversion of social norms, dedicated to the god Saturn.

Within this rich tapestry of belief and tradition emerges the figure of Diana. In Roman mythology, Diana was a goddess associated with the hunt, the moon, childbirth, and wild animals. She was often depicted as a powerful, independent woman, clad in hunting attire, with a bow and arrows slung over her shoulder. Her presence evoked the untamed wilderness, the silver glow of the moon, and the primal instincts of nature. She was a protector of the wild, a symbol of feminine strength and autonomy. It is important to view these descriptions not as literal attributes of a divine being, but as symbolic representations of concepts that held meaning for the people who conceived them. Diana’s association with the moon, for instance, could symbolize cycles, intuition, and the hidden aspects of existence. Her role as a huntress might represent skill, precision, and the respect for the delicate balance of the natural world.

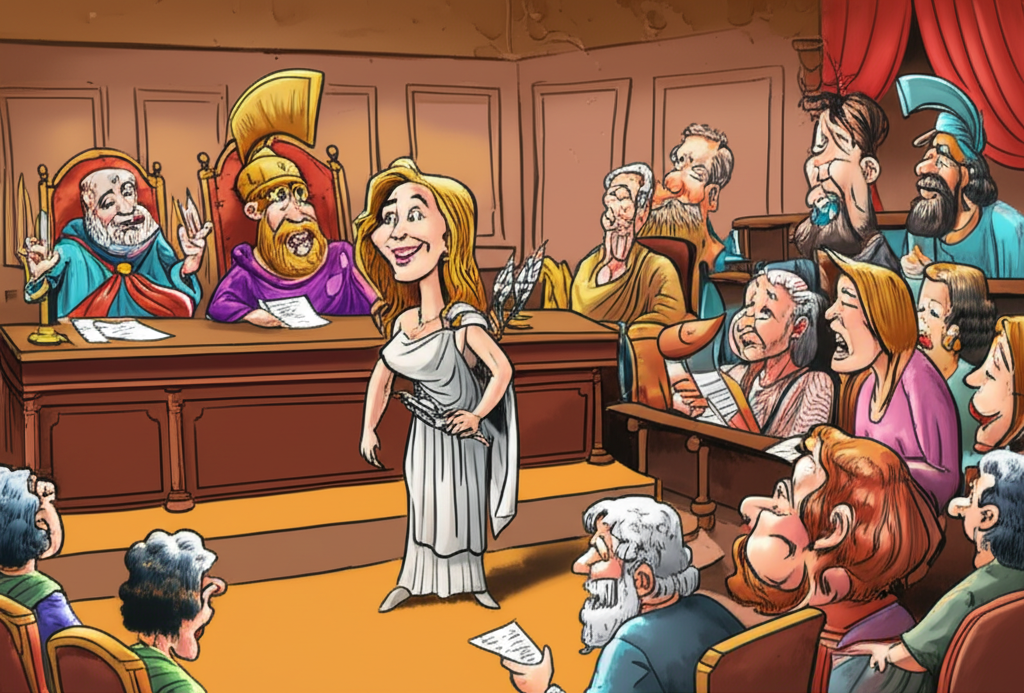

The narrative of Diana and the Trial of Saturnalia, as it might have been told, unfolds against the backdrop of this ancient Roman festival. Imagine the scene: the winter solstice approaches, and the city of Rome is abuzz with anticipation for Saturnalia, a time when masters would serve their slaves, gambling was permitted, and a general air of merriment prevailed. It was during this period of joyous chaos that Diana, the goddess of the wild and the moon, found herself facing a unique challenge.

According to the lore, the spirit of Saturnalia itself, a boisterous and untamed entity born from the collective joy and abandon of the festival, presented Diana with a trial. This spirit, not a singular being but an embodiment of the festival’s essence, was said to be capricious and demanding, testing those who dared to invoke its favor or seek its blessings. The trial was not one of physical combat, but a test of wit, empathy, and understanding of the human heart, particularly during a time of enforced equality and revelry.

Diana, ever observant of the natural world and the creatures within it, was asked to discern the true desires of mortals during Saturnalia. The challenge was to distinguish between genuine joy and fleeting amusement, between true generosity and performative kindness, and between the underlying anxieties that might surface even amidst celebration. The spirit of Saturnalia, in its playful yet profound way, presented her with a series of scenarios: a wealthy merchant feigning generosity to his slaves, a child experiencing genuine wonder at the festive lights, a lonely soul finding solace in the communal revelry, and a craftsman finding inspiration in the unusual freedom of the day.

Diana, with her keen senses honed by years of observing the subtle nuances of the wild, was tasked with identifying the purest expression of Saturnalia’s spirit in each instance. It was said she did not rely on divine pronouncements, but on her innate understanding of empathy, her ability to perceive the unspoken emotions that flickered in the eyes of mortals. She might have identified the child’s unadulterated delight as the most authentic, or perhaps the quiet act of comfort offered by one reveler to another. Her judgment was not about punishment or reward in a divine sense, but about recognizing the authentic pulse of humanity amidst the grand spectacle. The success of her trial was not marked by a divine victory, but by a deeper understanding of the human condition, a wisdom that even a goddess could gain from observing the fleeting moments of mortal experience.

The symbolism embedded within this narrative is multifaceted. Diana, as a representative of nature and the lunar cycles, could symbolize the inherent order and rhythm that underlies even the most chaotic celebrations. Her trial might have represented the ancient human desire to find meaning and authenticity within societal rituals. The spirit of Saturnalia, in its inversion of norms, could symbolize the human need for release, for a temporary escape from the rigid structures of everyday life, and the exploration of empathy and shared humanity. The story may have served as a moral compass, encouraging reflection on genuine kindness and the discerning of true emotions, even within times of revelry and social upheaval.

In the modern era, stories like Diana and the Trial of Saturnalia continue to resonate, albeit in different forms. These ancient myths are a fertile ground for literary inspiration, appearing in novels, poetry, and academic studies exploring classical civilizations. They find new life in the realms of fantasy and role-playing games, where characters inspired by Diana and the themes of ancient festivals are reimagined for contemporary audiences. In cultural studies, these narratives offer invaluable insights into the beliefs, values, and social structures of past societies, allowing us to understand how people made sense of their world.

It is vital to reiterate that Diana and the Trial of Saturnalia is a testament to human creativity and the enduring power of storytelling. As Muslims, we understand that only Allah, the Almighty, is the true Creator and Sustainer of all existence. Our faith teaches us to recognize the divine as singular and absolute, beyond the anthropomorphic interpretations found in ancient mythologies. Yet, these stories, born from the fertile imagination of ancient peoples, hold a significant place in our understanding of cultural heritage. They offer a window into the human drive to explain the world, to celebrate life, and to grapple with the complexities of existence. Through these narratives, we appreciate the richness of human imagination and the timeless tradition of passing down stories that, while not divine truth, illuminate the journey of human thought and culture across the ages.