Across the archipelago of the Philippines, where emerald islands rise from the cerulean embrace of the sea and ancient forests whisper secrets to the wind, a rich tapestry of myths and legends has been woven through generations. These are not divine scriptures but rather the imaginative tales of ancient peoples, attempts to explain the wonders and terrors of their world through stories passed down from elder to child. Among these captivating narratives is the myth of Bathala, the supreme deity in some pre-colonial Philippine mythologies, and the colossal serpent known as Bakunawa, whose alleged pursuit of the moon has shaped the very rhythm of the night. This story, born from a time when the cosmos was a canvas for wonder and the unseen held immense sway, offers a glimpse into the worldview of those who first navigated these islands.

The cultural milieu in which this myth likely took root was one deeply connected to the natural world. Before the advent of modern science, the celestial bodies were not mere astronomical objects but potent forces, their movements dictating seasons, tides, and agricultural cycles. The ancient Filipinos, living in close harmony with the land and sea, observed the moon’s phases with profound attention. Its waxing and waning, its journey across the inky expanse, was a spectacle of immense significance. Their understanding of the universe was often anthropomorphic and animistic, attributing spirits and intentions to natural phenomena. The sky was a realm populated by powerful beings, and the cycles of day and night, sun and moon, were seen as a grand drama unfolding above. This myth, therefore, can be understood as a personification of these observations, a narrative that gave agency and drama to the celestial dance.

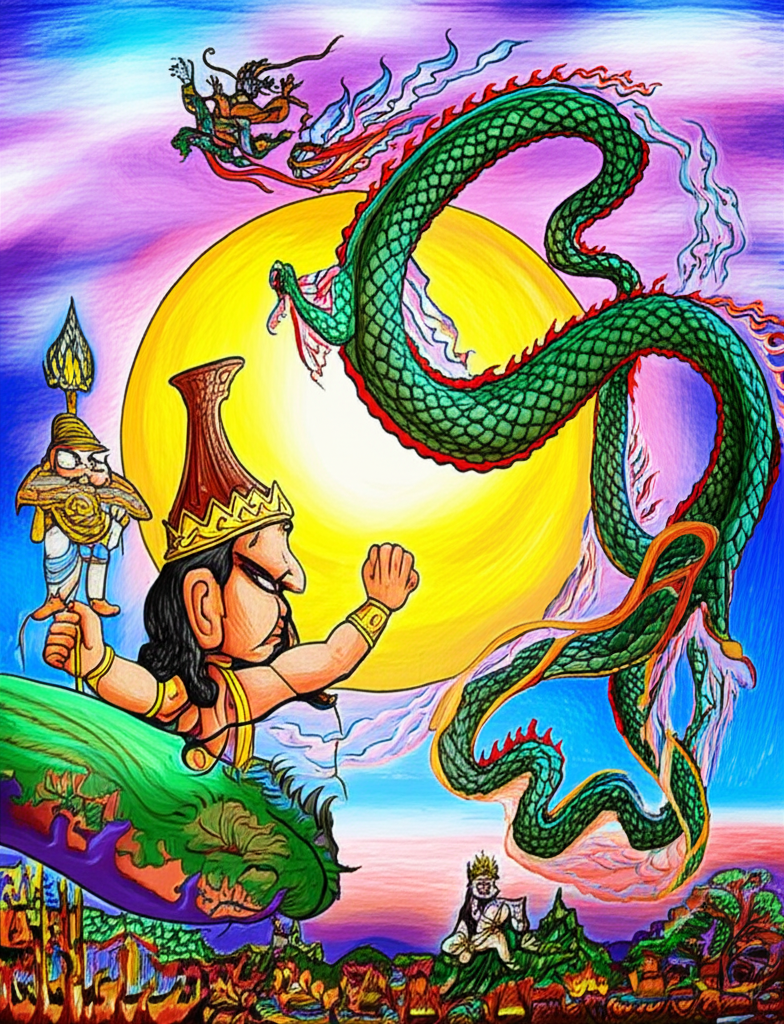

At the heart of this tale lies Bakunawa, a creature of immense scale and terrifying beauty, often depicted as a colossal sea serpent or dragon. Its form is said to be serpentine, adorned with scales that shimmer like the scales of a fish, perhaps reflecting the omnipresent sea that defined the lives of the islanders. Its eyes are described as fiery or luminous, capable of piercing the deepest darkness. Bakunawa is not presented as a benevolent entity but rather as a creature driven by an insatiable hunger, a primal force of desire. Its symbolic attribute is often associated with the abyss, the unknown depths of the ocean, and the primal fears that lurk in the darkness. It represents the chaotic forces of nature, the untamed elements that could threaten human existence. The very mention of its name conjures images of immense power and a primal urge that transcends rational understanding.

The narrative of Bakunawa’s journey with the moon, as recounted by the elders, begins in the celestial sphere. According to these ancient tales, Bakunawa, a creature of immense power residing in the primordial waters, developed an unyielding craving for the luminous moon. It was not just a fleeting desire, but a deep-seated longing, perhaps for its ethereal light, its gentle glow that soothed the darkness. Driven by this immense appetite, Bakunawa would ascend from its watery domain, its colossal form slithering through the night sky. The story paints a vivid picture: as the moon begins its ascent, Bakunawa follows, its enormous body eclipsing stars, its fiery eyes fixed on its luminous prize.

The climax of the story occurs when Bakunawa attempts to devour the moon. The people on Earth, witnessing this terrifying spectacle, would erupt in a cacophony of noise. They would bang on pots and pans, shout and clang their implements, creating a deafening din. This was not an act of worship, but a desperate plea, a collective effort to frighten the monstrous serpent away. The sheer volume of their noise, the story suggests, would startle Bakunawa, causing it to release its grip on the moon and retreat back into the ocean depths, its hunger temporarily sated or its pursuit thwarted. This act of communal outcry was believed to protect the moon and, by extension, the world from being plunged into eternal darkness. The cycle would then repeat, with Bakunawa’s return and the people’s continued vigilance.

This myth, in its ancient context, likely held multifaceted symbolic meanings. The moon itself, with its predictable cycles of growth and decline, could have represented order, time, and perhaps even feminine energy. Bakunawa, on the other hand, embodied chaos, the primal fears associated with the unknown – the deep sea, the darkness of night, and the destructive potential of nature. The story then becomes a narrative about the eternal struggle between order and chaos, light and darkness, a constant tension that needed to be managed and vigilantly guarded. The communal act of making noise can be seen as a representation of human agency, the collective will to protect their world from overwhelming forces, demonstrating that even in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges, human unity and action could make a difference. It was a way of understanding and coping with the natural world’s unpredictable and often frightening phenomena.

In the modern era, the myth of Bakunawa and the moon continues to resonate, albeit in different forms. It has been immortalized in literature, art, and popular culture, serving as a rich source of inspiration. Filipino authors have incorporated these figures into their novels and poems, exploring themes of cultural identity and the enduring power of ancestral stories. In visual arts, artists have depicted Bakunawa in striking imagery, capturing its fearsome grandeur. Moreover, the myth has found its way into contemporary entertainment, appearing in video games and animated films, allowing new generations to engage with this captivating folklore. These interpretations often highlight the visual drama of the story, the epic struggle between the serpent and the moon, while also delving into the deeper symbolic meanings that have captivated audiences for centuries.

It is crucial to reiterate that the story of Bathala and Bakunawa is a product of ancient storytelling, a testament to the imaginative capacity of early Filipino societies. As Muslims, we recognize that the ultimate Creator and Sustainer of all existence is Allah (SWT), the One God, who has no partners or equals. Our understanding of the universe is rooted in divine revelation and the teachings of the Quran and Sunnah.

Nevertheless, the myth of Bakunawa and the moon serves as a valuable cultural artifact, offering profound insights into the worldview, beliefs, and anxieties of the people who first inhabited the Philippines. It is a powerful reminder of our shared human heritage, the universal need to make sense of the world around us through narrative and imagination. These ancient tales, passed down through generations, are not mere superstitions but vibrant threads in the rich tapestry of human culture, celebrating the enduring power of storytelling and the indelible mark it leaves on our collective consciousness. They remind us of the boundless creativity of the human spirit and its ability to find meaning and wonder in the grand spectacle of the cosmos.