In the tapestry of ancient Japanese folklore, woven with threads of nature, reverence, and the celestial, lies a narrative that echoes through time: the story of Amaterasu’s cave. This is not a historical account, nor a divine decree, but a traditional tale, passed down through generations, offering a glimpse into the worldview of ancient peoples and their imaginative attempts to explain the world around them. From the mist-shrouded mountains to the sun-drenched plains, these stories served as both entertainment and a means of understanding the profound forces that shaped their lives.

The genesis of this particular myth can be traced to the early periods of Japanese history, a time when the lines between the human and the divine were far more fluid. This era, often referred to as the Jomon and Yayoi periods, was characterized by a deep connection to the natural world. Societies were largely agrarian, their lives intimately tied to the rhythms of the seasons, the fertility of the soil, and the unpredictable power of the elements. The world was viewed as a realm inhabited by spirits, or kami, residing in mountains, rivers, trees, and the very fabric of existence. Natural phenomena were not merely physical occurrences but were imbued with agency and often understood through anthropomorphic narratives. The sun, a source of life and warmth, was a particularly potent symbol, and it is within this context that the story of Amaterasu, the sun goddess, takes root.

Amaterasu, in this ancient pantheon, is depicted as a radiant and benevolent deity, the embodiment of the sun itself. Her symbolic attributes are intrinsically linked to light, warmth, growth, and order. She is often described as possessing a brilliant, life-giving radiance, representing the dawn that dispels darkness and the sun that nourishes all living things. Her celestial nature signifies purity, royalty, and the cosmic order that governs the universe. It is important to understand these descriptions not as claims of divinity, but as metaphorical representations of natural forces and societal ideals that ancient people sought to personify and understand.

The narrative of Amaterasu’s cave, a central piece of Japanese mythology, recounts a period of profound darkness that befell the land. The story goes that Amaterasu, the luminous sun goddess, was deeply angered or perhaps saddened by the unruly behavior of her brother, Susanoo-no-Mikoto, the god of storms and seas. In her distress, she retreated into a celestial cave, a place of profound darkness, and sealed herself within. With her withdrawal, the world was plunged into an unending night. The sun’s light vanished, and with it, warmth, growth, and joy. Plants withered, harvests failed, and despair spread across the land. The creatures of the world, accustomed to the sun’s life-giving embrace, huddled in fear and confusion.

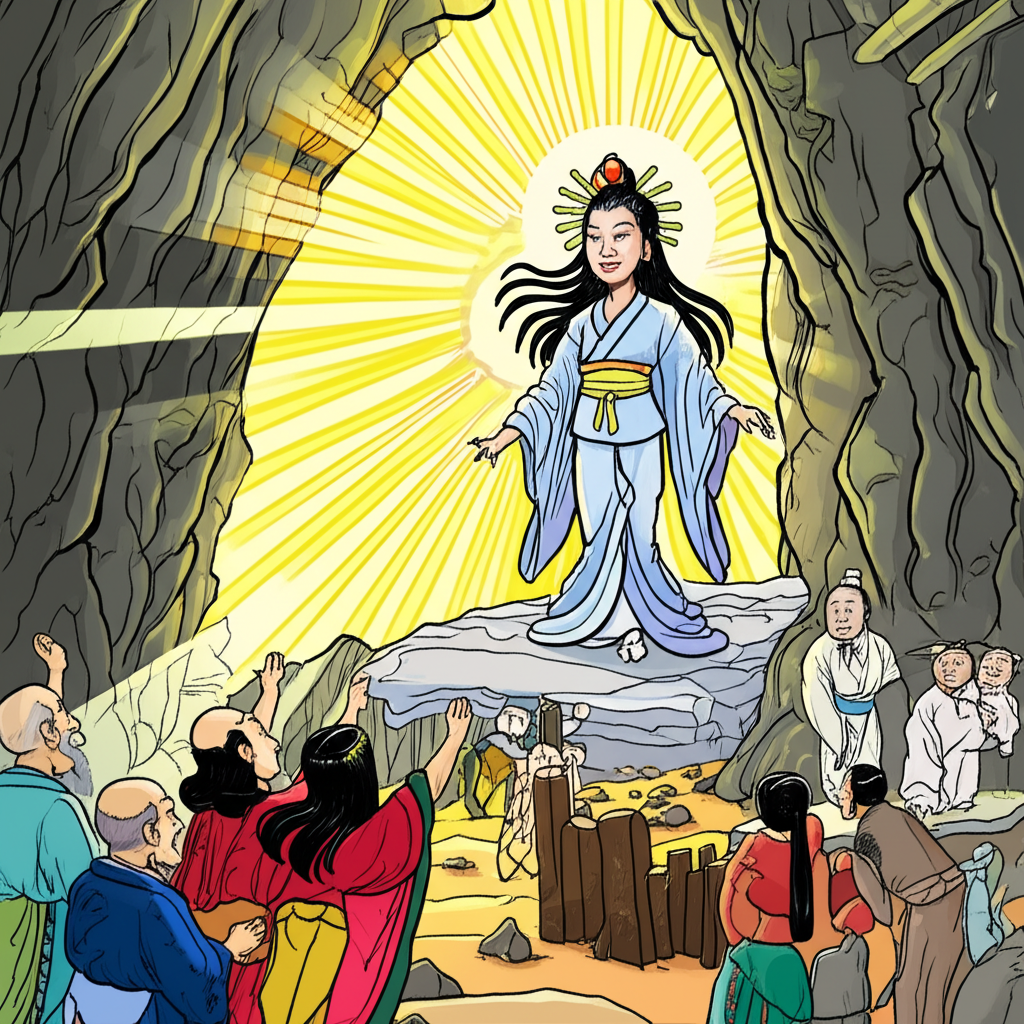

The gods and goddesses, in their desperation, gathered to devise a plan to lure Amaterasu out of her self-imposed exile. They devised a grand festival, a spectacle of sound and revelry. One of the goddesses, Ame-no-Uzume, a playful and vibrant spirit, performed a comedic dance that so amused the other deities that their joyous laughter echoed through the heavens. A mirror was then placed at the cave’s entrance, reflecting Amaterasu’s own brilliance. Intrigued by the commotion and the reflection of what seemed to be another sun, Amaterasu peeked out. As she emerged, her blinding radiance, once again visible, dispelled the darkness, and light returned to the world.

This vivid narrative, rich with personification, may have represented several profound concepts to the ancient Japanese. The withdrawal of Amaterasu into the cave can be seen as a symbolic representation of periods of hardship, natural disasters, or societal upheaval that plunged communities into metaphorical darkness. Her return, facilitated by the collective efforts of the other deities and the allure of light and joy, could symbolize the resilience of nature and the human spirit, the eventual overcoming of adversity, and the restoration of order. The mirror, reflecting her own light, might speak to the idea of self-discovery or the recognition of one’s own strength even in moments of doubt. Ame-no-Uzume’s dance highlights the power of mirth and communal celebration in lifting spirits and fostering hope.

In the modern world, these ancient myths continue to resonate, albeit in different forms. The story of Amaterasu and her cave has been retold and reinterpreted in countless ways. It appears in Japanese literature, inspiring epic poems and dramatic retellings. In popular culture, elements of this mythology can be found in anime, manga, and video games, where the characters and themes are adapted for contemporary audiences. These interpretations often explore the archetypal themes of light versus darkness, the consequences of divine discord, and the enduring power of hope. Cultural studies scholars also examine these myths to understand the historical development of Japanese religious beliefs, social structures, and artistic expressions.

In conclusion, the narrative of Amaterasu’s cave is a captivating example of the storytelling traditions of ancient Japan. It is a cultural artifact, a testament to the imagination and the profound desire of early peoples to understand their world and their place within it. As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah, the Almighty, is the true Creator and Sustainer of all that exists. These ancient tales, however, offer us a valuable window into the diverse ways humanity has sought meaning and expressed itself through stories, preserving a rich cultural heritage that continues to inform and inspire us. The echoes of these ancient narratives, like the whispers in a sacred grove, remind us of the enduring power of human imagination and the multifaceted tapestry of cultural expression.