The whispers of ancient Greece, carried on the winds that swept across sun-drenched islands and through the shadows of rocky valleys, tell tales of gods and mortals, of love and wrath, of impossible feats and enduring legends. Among these narratives, the story of Heracles and his twelve arduous labors stands as a testament to human resilience and divine intervention. Yet, at the heart of this epic saga lies a potent force, a celestial queen whose enduring resentment forged the very trials that would define a hero: Hera.

This is not a recounting of divine decree to be obeyed, nor a historical event to be verified. These are stories, woven from the threads of human imagination and cultural understanding, passed down through generations by the ancient Greeks to explain the world around them, their fears, and their aspirations.

Echoes of the Bronze Age: A World of Gods and Mortals

The myths of ancient Greece emerged from a civilization that flourished millennia ago, during the Bronze Age and beyond. Their world was one where the lines between the tangible and the supernatural were blurred. The vast expanse of the sky, the rumble of thunder, the unpredictable fury of the sea – these phenomena were not merely natural occurrences but manifestations of powerful, anthropomorphic deities. These gods, with their own intricate relationships, rivalries, and passions, were seen as shaping human destiny.

In this environment, where life could be fleeting and the forces of nature awe-inspiring, the Greeks sought to understand their place in the cosmos. They created elaborate mythologies not to dictate religious dogma in the way modern religions do, but to explore universal themes: the struggle for survival, the nature of justice, the consequences of hubris, and the yearning for glory. The stories were shared through oral tradition, epic poems like Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and later, through dramatic plays and sculptures. These narratives provided a moral framework, explained the origins of customs and natural phenomena, and offered a pantheon of figures whose exploits, both noble and flawed, resonated deeply with the human condition.

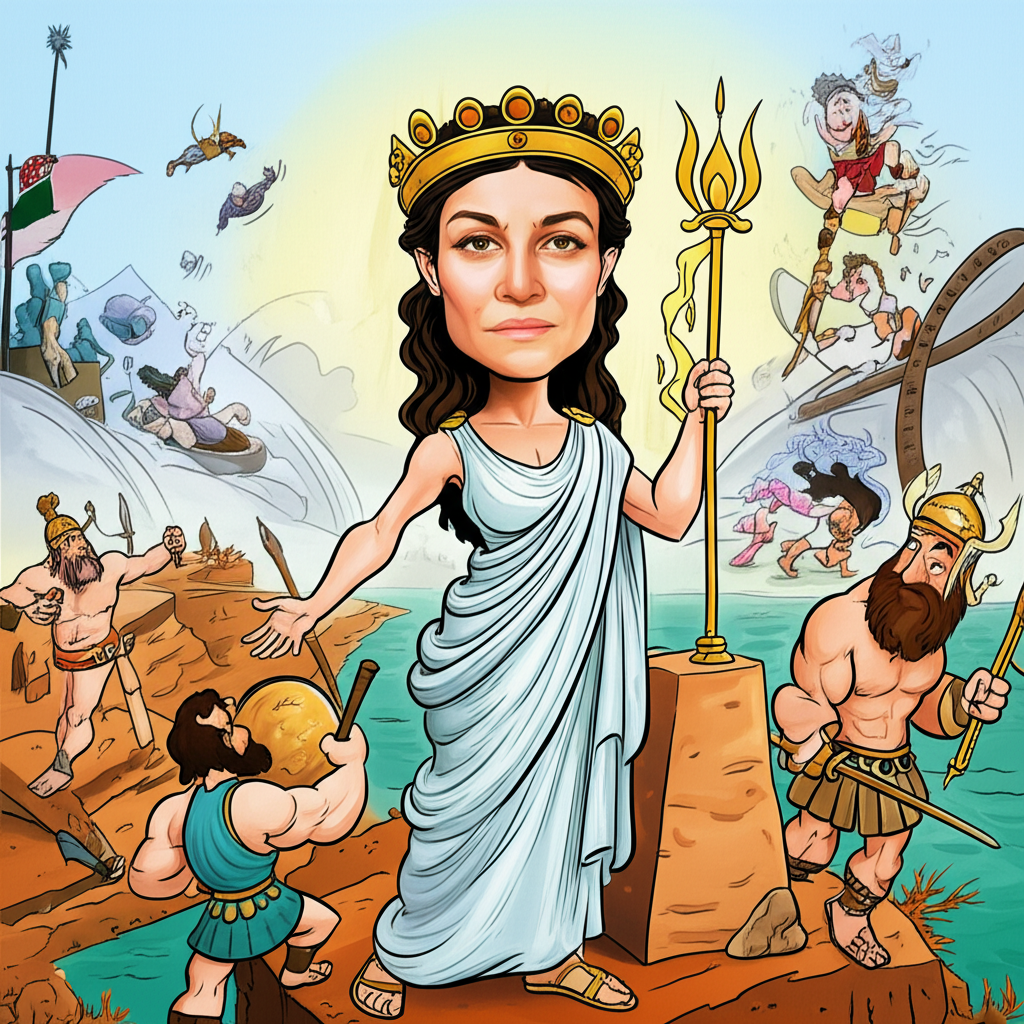

Hera: Queen of Olympus, Embodiment of Marital Fury

Hera, in these ancient narratives, is the formidable Queen of the Olympian gods, wife and sister to Zeus, the king of the gods. She is often depicted as a woman of immense beauty and regal bearing, adorned with a diadem and a scepter, signifying her supreme authority. Her symbolic attributes are manifold: the peacock, with its myriad eyes representing her watchful vigilance; the cow, a symbol of motherhood and domesticity, yet also of her fierce protectiveness; and the lily, an emblem of purity and feminine grace, which contrasts sharply with her volatile temper.

Hera’s power is not derived from brute force, but from her authority as queen and her formidable will. She embodies the complexities of marriage and the anxieties surrounding fidelity. While she is the goddess of marriage and childbirth, her most prominent characteristic in myth is her relentless jealousy and vengeful wrath, particularly directed towards any woman who caught Zeus’s wandering eye, and their offspring. She represents the power of a wronged woman, a force to be reckoned with, whose anger could shake the very foundations of the divine realm and impact the lives of mortals profoundly.

The Genesis of Suffering: Zeus’s Infidelity and Hera’s Vow

The story of Heracles’ labors is inextricably linked to Hera’s deep-seated animosity towards the hero, born from his very conception. Heracles, or Alcides as he was known before his heroic deeds, was the son of Zeus and a mortal woman, Alcmene. Zeus, in his pursuit of Alcmene, had disguised himself and deceived her. Hera, discovering Zeus’s latest infidelity, was consumed by a rage that knew no bounds. Her fury was not directed solely at Zeus, but with a particular intensity at the innocent offspring of his transgression.

Hera’s wrath manifested in various attempts to thwart Heracles from birth. She sent serpents to his cradle, which the infant hero famously strangled with his bare hands. However, it was after Heracles had grown into a formidable man, renowned for his strength and courage, that Hera’s most devastating plan was conceived. Driven by her enduring hatred, Hera, through a complex series of divine machinations and by exploiting Heracles’ own tragic circumstances, orchestrated a situation where Heracles, in a fit of madness (often attributed to Hera’s influence), killed his own wife and children.

Devastated and consumed by guilt, Heracles sought purification and guidance from the Oracle of Delphi. The oracle, acting as a conduit for divine pronouncements, decreed that Heracles must serve King Eurystheus of Tiryns for twelve years and perform ten tasks set by him. However, Eurystheus, a weak and cowardly king, was himself a pawn of Hera. He was heavily influenced by the goddess and often doubled the tasks or made them impossibly dangerous, knowing Hera would be pleased by Heracles’ suffering. Thus, the legendary twelve labors of Heracles were born, not as a testament to his inherent destiny, but as a bitter penance and a prolonged torment orchestrated by a vengeful goddess.

The Twelve Ordeals: A Test of Endurance and Divine Opposition

The narrative of the labors is a grand tapestry of heroic struggle against overwhelming odds, each task a meticulously crafted challenge designed to break the hero. These were not simple chores; they were encounters with monstrous beasts, impossible feats of strength, and journeys into the very heart of fear and the unknown, often with Hera subtly or overtly hindering his progress.

There was the Nemean Lion, whose hide was impervious to mortal weapons, forcing Heracles to wrestle it into submission. Then came the Lernaean Hydra, a multi-headed serpent whose severed heads grew back in double, a task requiring cunning as much as strength, with Hera’s sacred snakes often seen as aiding the Hydra. He cleansed the Augean Stables, a task of immense filth that required diverting rivers, showcasing his ingenuity. He captured the Ceryneian Hind, a sacred deer with golden antlers, a test of pursuit and respect for the divine. He cleared the Stymphalian Birds, creatures with bronze beaks and feathers, from a lake, requiring him to use a rattle given by Athena, another goddess who often favored Heracles, contrasting Hera’s animosity.

His labors continued with capturing the Cretan Bull, a raging beast; taming the Mares of Diomedes, flesh-eating horses; retrieving the Girdle of Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons, a task that involved navigating complex diplomatic and martial encounters; obtaining the Cattle of Geryon, a monstrous three-bodied giant; stealing the Apples of the Hesperides, guarded by a fearsome dragon and the titan Atlas; and finally, capturing Cerberus, the three-headed dog guarding the underworld. Each labor demanded not only immense physical prowess but also courage, intelligence, and perseverance, often under the invisible, yet palpable, weight of Hera’s malevolent gaze.

Symbolism in the Sands of Time: Nature, Morality, and Human Frailty

To the ancient Greeks, the myth of Heracles and his labors offered a rich tapestry of symbolic meaning. The monstrous creatures and impossible tasks often represented the untamed forces of nature that they sought to understand and control: the ferocity of wild animals, the overwhelming power of natural disasters, and the darkness of the unknown. Heracles, in overcoming these challenges, embodied the human aspiration to master their environment, to bring order to chaos, and to assert dominance over the primal forces that threatened their existence.

Furthermore, the story served as a profound exploration of morality and human frailty. Heracles’ initial act of violence, driven by divine madness, highlighted the consequences of unchecked emotions and the devastating impact of betrayal. His subsequent penance underscored the importance of atonement, perseverance, and the arduous path towards redemption. The labors also spoke to the concept of leadership and duty. Heracles, though a demigod, was bound by a vow and forced to serve a weak king, reflecting the complex realities of societal structures and the burdens of responsibility that often fall upon the strong. Hera, in her relentless pursuit of vengeance, represented the destructive power of envy and the enduring consequences of personal vendettas, serving as a cautionary tale about the destructive nature of unchecked emotion.

Modern Resonance: Echoes in Art and Narrative

In the modern era, the myth of Heracles and his labors continues to capture the imagination, echoing through various forms of art and storytelling. He remains a quintessential hero figure, a symbol of ultimate strength and perseverance, often depicted in literature, film, and video games. These interpretations often focus on the heroic aspects of his journey, his epic battles, and his eventual triumph, sometimes downplaying or reinterpreting the role of Hera. He appears as a character in epic fantasy, historical fiction, and even in more contemporary settings, where his trials are translated into metaphorical struggles against societal evils or personal demons. Art historians analyze the depictions of Heracles in ancient sculptures and pottery, while scholars of mythology explore the enduring themes and cultural significance of his story.

A Legacy of Stories, Not of Belief

It is crucial to reiterate that the narrative of Hera and the labors of Heracles is a traditional story, a product of ancient human imagination, and not a factual account or a divine mandate. As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah is the true Creator and Sustainer of the universe, and that all power and authority reside with Him alone. These ancient tales, while fascinating from a cultural and historical perspective, do not hold any divine truth.

The enduring power of these myths lies in their ability to reflect the human experience, our hopes, our fears, and our capacity for both incredible feats and profound suffering. The story of Hera’s grudge and Heracles’ labors is a testament to the rich tradition of storytelling that has shaped cultures for millennia, offering insights into the values, beliefs, and worldview of ancient peoples. It is a reminder of the boundless nature of human creativity and the enduring fascination with tales of heroes, monsters, and the complex interplay between the divine and the mortal. These stories, when viewed through the lens of cultural heritage, enrich our understanding of the past and the evolution of human thought, without ever compromising our fundamental beliefs.