1. Introduction

The tapestry of ancient Greek mythology is rich with tales of heroes, gods, and epic struggles that captivated the imaginations of people thousands of years ago. Among these legendary figures, Achilles stands as perhaps the most formidable warrior of his age, his name synonymous with unmatched prowess and a tragic destiny. While the core narratives surrounding Achilles, particularly his role in the Trojan War, are well-established, the specific tale of "Achilles and the Trial of Sparta" is not a widely documented canonical myth. Instead, for the purpose of this article, we embark on a narrative exploration, imagining a story that could have been woven within the vibrant mythological tradition of ancient Greece, a testament to the enduring human desire to test the limits of its greatest heroes. This narrative, like countless others from the era, is a traditional story crafted by ancient people (or in this case, inspired by their storytelling ethos) and is presented solely for cultural, historical, and educational understanding, not as a claim of truth or belief.

2. Origins and Cultural Background

This imagined narrative draws its essence from the cultural era of Bronze Age Greece, roughly spanning from 3000 to 1100 BCE, particularly the Mycenaean civilization, which formed the backdrop for many heroic myths. It was a time of powerful city-states, monumental fortresses, and a society deeply stratified, where kings and warriors held sway. The people of this era viewed their world through a polytheistic lens, believing in a pantheon of anthropomorphic gods and goddesses—Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Athena, Apollo, and many others—who resided on Mount Olympus and frequently intervened in human affairs, often with capricious will.

Life was seen as a delicate balance between human agency and divine decree, with fate (Moira) playing an inescapable role. Honor (timē), glory (kleos), and excellence (aretē) were paramount values, particularly for the aristocratic warrior class. Heroes were often demigods, favored or cursed by the Olympians, embodying the pinnacle of human potential and the tragic consequences of ambition and hubris. Oral tradition was the primary means of transmitting these stories, passed down through generations by bards and poets, shaping the collective identity and moral framework of their society. Warfare was a constant reality, and martial prowess was revered, making Sparta, with its legendary military discipline, a fitting setting for a hero’s ultimate test.

3. Character Description: Achilles and the Spirit of Sparta

At the heart of our narrative stands Achilles, the preeminent hero of the Achaeans. Son of the mortal king Peleus and the sea nymph Thetis, Achilles was destined for greatness from birth. His mother, seeking to render him immortal, dipped him into the River Styx, making his body invulnerable save for the heel by which she held him—his infamous "Achilles’ heel." He was trained by the centaur Chiron, mastering not only combat but also music and healing. Physically, Achilles was depicted as a figure of breathtaking beauty and terrifying power: golden-haired, swift-footed, and possessing a voice that could command or inspire dread. Symbolically, Achilles embodies the pinnacle of individual warrior excellence, divine favor, and the tragic flaw of overwhelming pride and a volatile temper. He represents the human yearning for eternal glory, even at the cost of a long life.

Sparta, though a city-state and not a "creature," serves as a formidable symbolic entity in this narrative. Known as Lacedaemon, Sparta was not merely a city but a way of life, a collective consciousness forged in an unyielding crucible of military discipline and civic duty. Its people, the Spartans, were legendary for their austerity, their laconic speech, their unwavering courage, and their absolute devotion to the state above all else. From birth, Spartan boys were groomed for war, undergoing the agoge, a brutal training regimen designed to strip away individuality and forge perfect soldiers. Sparta, in this context, symbolizes the ultimate trial of collective strength, rigid adherence to law, and the suppression of personal glory for the greater good. It is the antithesis of Achilles’ individualistic heroism, presenting a challenge not merely of strength, but of character, discipline, and the very definition of what makes a hero.

4. Main Story / Narrative Retelling

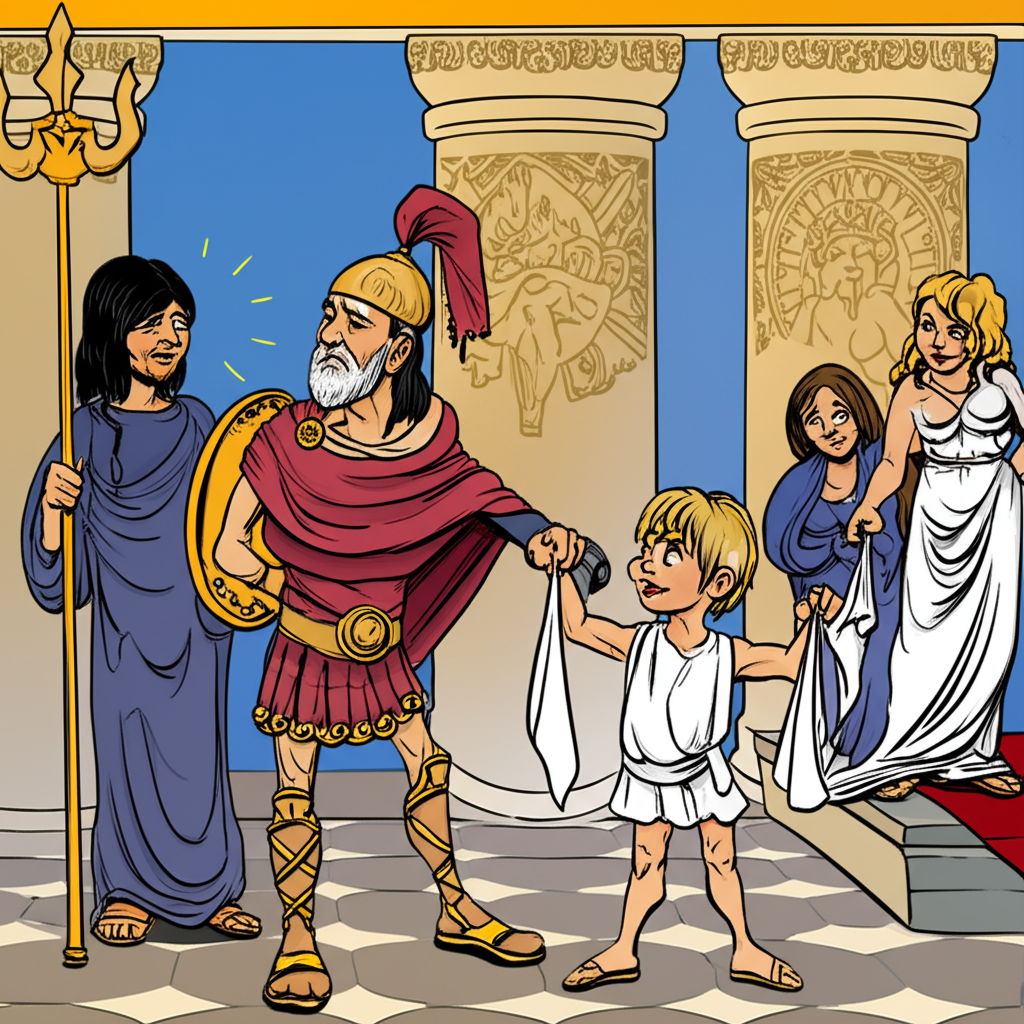

In the years before the great host sailed for Troy, when Achilles’ name already echoed across the Hellenic world, a quiet unease settled upon the kings of the Peloponnese. His unmatched strength was a marvel, yet his fierce independence and quick temper were a potential storm. King Menelaus of Sparta, known for his calm resolve, sought not to subdue Achilles, but to understand and, perhaps, to temper the fiery demigod. He extended an invitation, not for war, but for a "Trial of Spartan Virtue" – a challenge designed not for battlefield glory, but for the soul.

Achilles, ever eager for a test, arrived in Lacedaemon with a retinue, his bronze armor gleaming, his bearing one of proud defiance. The Spartans, clad in their crimson cloaks, watched with silent appraisal, their eyes betraying neither awe nor disdain. The trial, Menelaus explained, would consist of three parts, each designed to strip away the external trappings of heroism and reveal the true character beneath.

The first was the Trial of Endurance. For three days and three nights, Achilles was to traverse the treacherous Taygetus mountains, armed with only a single spear, a tunic, and a meager ration of dried figs. He was forbidden to hunt, to light a fire, or to seek shelter beyond what the harsh landscape offered. For a man whose invulnerability protected him from physical harm, this was a test not of vulnerability, but of spirit. The biting winds, the gnawing hunger, the relentless solitude—these were the true adversaries. Achilles, accustomed to the roar of battle and the comfort of his camp, chafed against the silent suffering. Yet, his will, as indomitable as his shield, pushed him onward. He returned, gaunt and weary, but unbroken, a new respect for the quiet fortitude of the Spartans etched into his gaze.

Next came the Trial of Discipline. Achilles was commanded to live for a week within a Spartan syssitia, a communal mess hall, and adhere strictly to the Spartan way. He was to eat the plain, unappetizing melas zomos (black broth), sleep on a hard reed mat, and participate in the rigorous training of the Spartan youth, submitting to the authority of their paidonomos (magistrate). This was perhaps the most challenging for the proud son of Thetis. To be ordered, to be admonished, to be treated as one among many, to suppress his individual brilliance for the sake of collective drills – it grated against his very nature. There were moments of simmering rage, of near-rebellion, yet the silent, unwavering stares of the Spartans, the sheer force of their communal will, held him in check. He learned to march in perfect synchronicity, to respond without question, to find a strange rhythm in the collective strength. He learned, too, that true power could lie not just in individual might, but in an unbreakable, unified front.

The final trial was the Trial of Sacrifice. Achilles was led to the agora, where a simulated battle was to take place. He was given command of a small detachment of Spartan warriors, tasked with defending a symbolic position against a larger "enemy" force. The catch: Achilles was forbidden to engage in single combat, forbidden to seek personal glory. His role was purely strategic, to lead, to organize, to ensure the survival of his men and the success of the mission, even if it meant remaining in the background. For the warrior who lived for the thrill of the duel, this was agony. His fingers itched for his sword, his heart yearned for the clash. Yet, he saw the unwavering trust in the eyes of the Spartan warriors under his command. He saw the intricate dance of their formations, the quiet obedience to his commands. He adapted, channeling his strategic genius, his understanding of terrain and movement, to orchestrate a flawless defense. He won the simulated battle, not by his own spear, but by the coordinated effort of his unit, a victory of collective wisdom over individual heroism.

Menelaus, observing from afar, finally approached Achilles. "You have faced trials of the body, the spirit, and the mind, son of Peleus," the king declared. "You have shown us that even the greatest among us can learn, can adapt, and can find strength in discipline and unity. You have not become a Spartan, Achilles, but you have understood the Spartan heart." Achilles, his gaze softer than it had ever been, nodded. He had not lost his individual fire, but he had glimpsed a different kind of strength, a truth that would subtly shape his leadership in the war to come. He departed Sparta, not as a changed man, but as a more complete hero, carrying a newfound appreciation for the quiet, unyielding power of the Lacedaemonians.

5. Symbolism and Meaning

This imagined narrative, like many traditional Greek myths, is rich with symbolism and meaning. For the ancient Greeks, Achilles’ journey through the "Trial of Sparta" would have represented a profound exploration of what truly defines a hero. It highlights the tension between individual glory versus collective good, a recurring theme in Greek thought. Achilles, the epitome of individual aristeia (excellence in battle), is forced to confront the Spartan ideal of absolute devotion to the polis (city-state) and the suppression of personal ambition.

The trials themselves symbolize different facets of human virtue:

- Endurance: The triumph of spirit over physical hardship, testing mental fortitude beyond mere invulnerability.

- Discipline: The necessity of self-control, obedience to law, and the strength derived from unity, challenging Achilles’ inherent pride and independence.

- Sacrifice: The understanding that true leadership sometimes requires stepping back from the limelight, prioritizing the well-being of the group over personal fame.

This story would have underscored the idea that even divine favor and immense strength are insufficient without wisdom, discipline, and a broader understanding of human cooperation. It might have served as a moral tale, suggesting that true heroism encompasses not only martial prowess but also character, resilience, and the capacity for growth.

6. Modern Perspective

In contemporary culture, the figures of Achilles and the ethos of Sparta continue to resonate deeply, albeit through different lenses. Achilles remains an archetype of the flawed hero, his story adapted in countless forms. In literature, films like "Troy" (2004) portray his emotional depth, his struggle with fate, and his tragic love, often emphasizing his human vulnerabilities over his divine strength. Video games frequently feature Achilles as a powerful warrior, allowing players to embody his legendary combat skills. His "Achilles’ heel" has become a common idiom, representing any fatal weakness.

Similarly, Sparta has captured the modern imagination, often glamorized in popular culture. Films like "300" (2006) depict the Spartans as ultimate warriors, epitomizing courage, discipline, and an unyielding will against overwhelming odds. In cultural studies, both Achilles and Sparta are examined as powerful symbols: Achilles as the embodiment of the individualistic, driven hero, and Sparta as the ultimate example of a collectivist, militaristic society. They offer enduring archetypes for exploring themes of heroism, sacrifice, the nature of war, and the complexities of human character in literature, philosophy, and popular entertainment. These narratives continue to provide rich ground for understanding human nature and societal ideals, even as their historical and mythological contexts are reinterpreted.

7. Conclusion

The narrative of "Achilles and the Trial of Sparta," whether a traditional myth or a creative exploration within the mythological framework, serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring human capacity for storytelling. These ancient tales, passed down through generations, were never meant to be factual accounts or objects of worship. Rather, they were cultural stories, imaginative constructs that helped ancient people understand their world, explore moral dilemmas, and define the virtues and vices they saw in themselves and their heroes.

As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah is the true Creator and Sustainer of all existence, and our belief is in His singular, absolute power and wisdom. These mythological narratives, therefore, are viewed not as divine truths but as fascinating cultural heritage—testaments to the human spirit’s quest for meaning through imagination and narrative. They offer insights into the values and worldview of civilizations long past, enriching our understanding of human history, literature, and the universal tradition of storytelling that transcends cultures and time, reflecting the diverse ways humanity has sought to comprehend its place in the world.