From the sun-baked sands and the life-giving embrace of the Nile, a tapestry of stories has been woven for millennia. These narratives, born from the fertile minds of ancient Egyptians, offer glimpses into their understanding of the cosmos, the human condition, and the forces they perceived to be at play in their world. Among these enduring tales, the myth of the Canopic Jars and their connection to the fearsome goddess Sekhmet whispers of ancient beliefs about life, death, and the preservation of the soul. This is a traditional story, passed down through generations, a testament to the imagination of a people who sought to comprehend the mysteries that surrounded them.

To understand this narrative, we must journey back to a time when the rhythm of life was dictated by the predictable flood of the Nile, the scorching heat of the desert sun, and the vast, star-dusted expanse of the night sky. Ancient Egyptian society was deeply intertwined with its environment. The fertile strip along the Nile was their lifeblood, providing sustenance and a stark contrast to the arid, unforgiving desert. Their worldview was one of profound duality: the ordered, life-sustaining world of the Nile Valley versus the chaotic, potentially dangerous realm of the desert. This duality extended to their understanding of the divine, with deities embodying both benevolent and destructive aspects. The afterlife was not an end, but a continuation, a journey that required careful preparation and the appeasing of powerful forces.

Central to this particular narrative is Sekhmet, a figure of immense power and primal ferocity. She is often depicted as a lioness, her gaze sharp and her presence radiating an almost palpable heat. This form is not meant to be believed in as a literal deity, but understood as a symbolic representation of potent, untamed forces. The lioness, a powerful predator, embodies destruction, plague, and the scorching heat of the sun that could wither life. Yet, Sekhmet also possessed a duality; she was the protector of the pharaoh and the patron of healers, capable of averting the very disasters she could unleash. Her symbolic attributes thus speak to the ancient Egyptians’ understanding of the volatile nature of existence – the ever-present possibility of both creation and annihilation, of healing and suffering, all contained within the potent forces of the universe.

The tale of the Canopic Jars, as it might have been recounted in ancient Egypt, speaks of a time when the gods, in their immense power, pondered the fate of humanity. It is said that Sekhmet, in her fiery wrath, was unleashed upon the world to punish mankind for their transgressions. The ensuing devastation was terrible, the land scorched, and a pervasive sickness spread like wildfire. The gods, witnessing the near annihilation, grew concerned that their creation would be lost forever. It was then that Ra, the sun god and often the supreme deity, sought a way to appease Sekhmet and halt her destructive rampage.

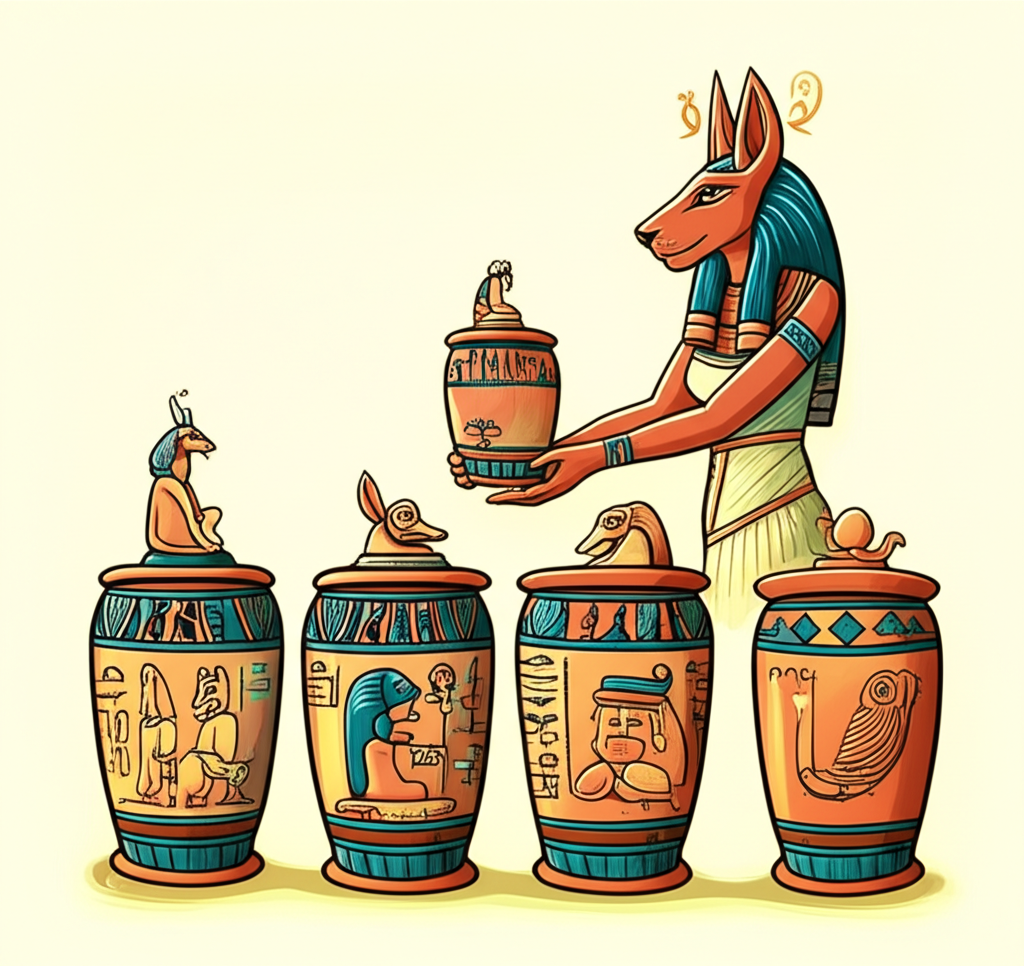

One version of the story suggests that Ra, understanding Sekhmet’s powerful, life-giving, yet also destructive, breath, conceived a plan. He gathered the four sons of Horus – Imsety, Hapi, Duamutef, and Qebehsenuef – each tasked with safeguarding a vital part of the deceased. Ra instructed them to fashion special vessels, crafted from precious materials and imbued with protective enchantments. These vessels, the Canopic Jars, were to be more than mere containers; they were to be receptacles for the vital organs that held the essence of life and spirit.

As Sekhmet’s rage continued to burn, Ra, with cunning and foresight, ordered the earth to be stained with red ochre and mixed with barley. This concoction, resembling blood and the fruits of the land, was then spread across the land in vast quantities. When Sekhmet, in her bloodlust, descended to continue her destructive work, she encountered this immense, alluring spectacle. Mistaking the ochre and barley for the blood of humanity, she began to drink deeply, her thirst for vengeance momentarily quenched. The sheer volume of the intoxicating mixture, however, rendered her inebriated and dulled her senses, effectively halting her destructive rampage.

In the ensuing calm, with Sekhmet pacified and her destructive power temporarily subdued, the gods entrusted the four sons of Horus with a sacred duty. They were to carefully extract the vital organs – the liver, lungs, stomach, and intestines – from those who had perished. These organs, believed to hold a crucial part of a person’s spirit and life force, were then placed into the specially prepared Canopic Jars. Each jar was guarded by one of the sons of Horus and symbolically protected by one of the four cardinal directions. Imsety, with his human head, guarded the liver; Hapi, with his baboon head, protected the lungs; Duamutef, with his jackal head, was responsible for the stomach; and Qebehsenuef, with his falcon head, watched over the intestines. These jars, filled with the essence of life, were then placed within the tomb, ensuring that the deceased’s earthly vessel could be reunited with its spiritual components in the afterlife. The story thus positions the Canopic Jars not as a gift of Sekhmet in a benevolent sense, but as a consequence of her power, a necessary measure taken to preserve what remained of humanity after her near-annihilation, a testament to the gods’ intervention to mitigate her devastating impact.

The symbolism woven into this narrative is rich and multifaceted. Sekhmet’s dual nature, as both destroyer and protector, reflects the ancient Egyptians’ understanding of the inherent volatility of life and the universe. The scorching sun that could bring life or death, the plagues that could decimate populations, and the potential for healing all found expression in her form. The Canopic Jars themselves represented a profound belief in the continuation of life beyond death. The meticulous preservation of the organs was not merely a ritualistic act but a practical necessity for the deceased’s journey through the underworld and their eventual rebirth. The four sons of Horus, each with their specific protective role, embodied the structured order the Egyptians sought to impose on the chaos of death. The story, therefore, speaks to themes of divine power, the consequences of unchecked wrath, the necessity of preservation, and the hope for an enduring existence.

In the modern world, these ancient narratives continue to resonate, albeit in vastly different contexts. The Canopic Jars, once objects of profound religious significance, are now primarily studied by archaeologists, historians, and cultural anthropologists. They feature prominently in museum exhibits, captivating audiences with their intricate craftsmanship and the stories they represent. In literature, film, and video games, ancient Egypt and its mythology frequently serve as backdrops for adventure and intrigue. Sekhmet, in particular, often appears as a formidable antagonist or a powerful, enigmatic force, her leonine ferocity a compelling visual and narrative element. The concept of mummification and the preservation of the body, including the use of Canopic Jars, continues to fuel our fascination with ancient practices and the enduring human quest to understand death and the afterlife.

It is crucial to reiterate that the tale of Sekhmet and the Canopic Jars is a cultural story, a product of ancient human imagination seeking to explain the world and their place within it. As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah is the true Creator and Sustainer of all existence, the ultimate source of power and life. These ancient narratives, while fascinating from a historical and cultural perspective, do not alter this fundamental truth. Yet, as we delve into these stories, we gain a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of human heritage, the power of storytelling to convey meaning, and the enduring human capacity for imagination, even in the face of the profound mysteries of life and death. These ancient myths, like the desert winds, carry echoes of the past, reminding us of the diverse ways humanity has sought to understand its world and its place within the grand, unfolding narrative of existence.