Introduction

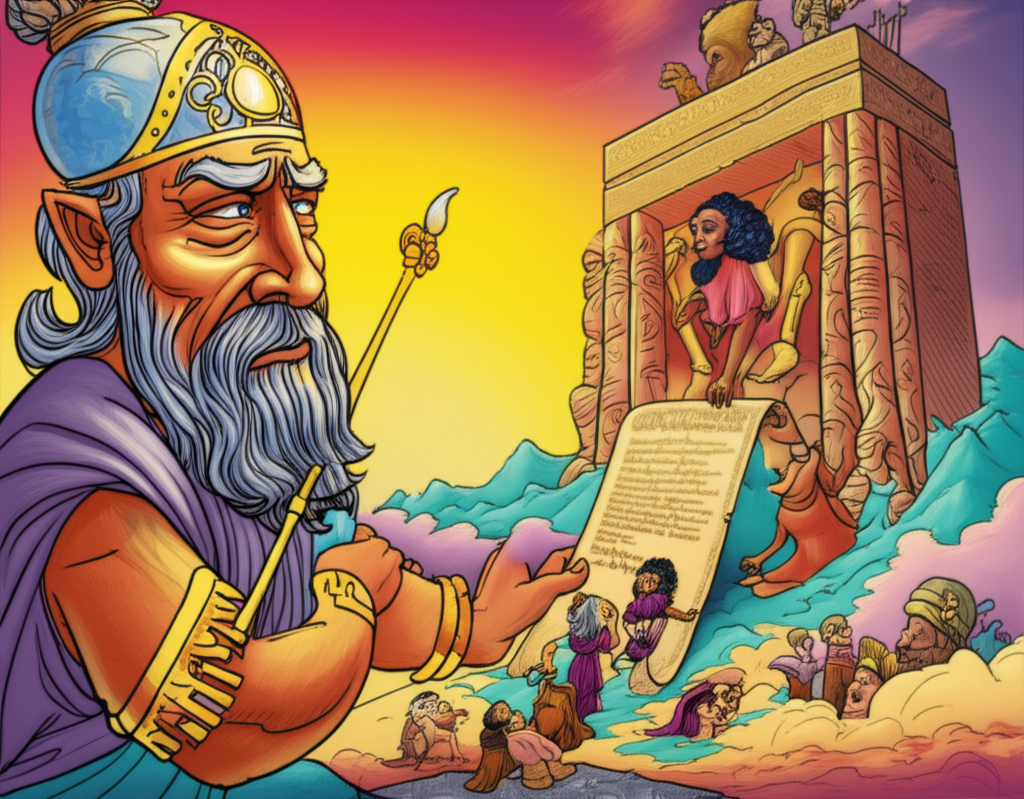

From the sun-scorched river plains of ancient Mesopotamia, a land cradled between the Tigris and Euphrates, emerge some of humanity’s oldest recorded stories. Etched into clay tablets in the intricate cuneiform script, these tales give us a profound window into the minds of the Sumerians, Akkadians, and Babylonians. Among their most enduring and dramatic narratives is the myth of the goddess Inanna’s descent into the underworld. It is a powerful traditional story told by these ancient people to explore themes of ambition, loss, and the cyclical nature of life and death. This particular retelling focuses on the critical role of the great god Enlil, whose unyielding judgment formed a pivotal moment in this cosmic drama.

Origins and Cultural Background

This myth originates in the Sumerian civilization, flourishing over 4,000 years ago in what is now modern-day Iraq. The Sumerians lived in a world dictated by the rhythms of agriculture and the often-unpredictable forces of nature. The rivers could bring life-giving water or devastating floods; the sun could nurture crops or scorch the earth. To make sense of this reality, they envisioned a pantheon of powerful deities who embodied these forces. Their gods were not distant, perfect beings but were portrayed with human-like emotions: jealousy, ambition, wisdom, and wrath. The world was a stage for divine politics, and humanity’s fate was often tied to the whims and decrees of these figures. The underworld, known as Kur or Irkalla, was not a place of punishment but a bleak, dusty realm of shadows from which no traveler, mortal or divine, was meant to return.

Character Description

Inanna (later known as Ishtar) was one of the most complex and revered figures in the Mesopotamian pantheon. As the Queen of Heaven, she was the goddess of love, fertility, and beauty, often depicted as a radiant and desirable figure. However, she also possessed a formidable and fearsome aspect as a goddess of war, political power, and strategic conquest. Her ambition was boundless, and her stories often depict her striving to expand her influence. Her primary symbols were the eight-pointed star, representing the morning and evening star (the planet Venus), and the lion, signifying her untamable strength and regal authority. In this myth, Inanna symbolizes not just a deity, but the unquenchable drive for knowledge and power, even at the greatest possible cost.

Enlil, whose name means "Lord of the Wind" or "Lord of the Air," was a member of the supreme triad of gods, alongside his father Anu (the sky) and his brother Enki (the water and wisdom). Enlil was the god of the atmosphere, the breath of life, and the earth’s surface. He was the enforcer of the divine order, the keeper of the Tablets of Destiny, which decreed the fate of gods and mortals alike. While sometimes a benefactor who granted kingship, he was more often depicted as a stern, impartial, and sometimes harsh authority figure. He was the force behind the great flood in other myths, a decision made to quiet a noisy humanity. In this story, Enlil represents the unbendable structure of cosmic law—the idea that some rules are absolute and must not be broken, not even for the most beloved of goddesses.

Main Story: The Narrative Retelling

According to the ancient tablets, the great goddess Inanna, Queen of Heaven and Earth, stood at the zenith of her power. Yet, her ambition knew no bounds. In her heart, she made a solemn oath to herself: she would conquer the one realm that lay beyond her grasp—the Great Below, the desolate underworld ruled by her formidable elder sister, Ereshkigal. It was a kingdom of dust and silence, and Inanna intended to claim it.

Knowing the journey was perilous, she prepared meticulously. She adorned herself with the seven divine powers, or me, manifesting as her crown, beads, robes, and other articles of power. Before departing, she gave strict instructions to her faithful vizier, Ninshubur. "If I do not return in three days and three nights," she commanded, "you must raise a lament for me. Go to the great temples. Go first to Nippur, to the temple of Enlil. Plead with him not to let his daughter perish in the underworld. If he refuses, go to Ur and plead with the moon god Nanna. If he too refuses, go to Eridu, to the temple of the wise Enki. He who knows the secrets of life and death will surely devise a plan."

With her oath set, Inanna descended. She arrived at the first of the seven gates of the underworld, her presence announced to the fearsome Ereshkigal. Enraged by her sister’s audacity, Ereshkigal commanded her gatekeeper, Neti, to enforce the laws of the Great Below. "As each guest enters," she decreed, "they must be stripped bare."

At each of the seven gates, Inanna was forced to remove one of her divine articles. Her crown was taken at the first gate, her lapis lazuli beads at the second, and so on, until she stood naked and powerless before Ereshkigal’s throne. The Anunnaki, the seven dreadful judges of the underworld, passed their sentence. Ereshkigal fixed upon her the eye of death, spoke a word of wrath, and Inanna became a corpse, hung from a hook on the wall.

Three days and three nights passed. On the earth above, Ninshubur, seeing her queen had not returned, began the lamentations. As instructed, she traveled first to the great city of Nippur and prostrated herself before Enlil.

"Oh, Father Enlil," she cried, "do not let your daughter be put to death in the underworld! Do not let your precious lapis lazuli be covered with the dust of Kur! Do not let your fine boxwood be chopped into pieces for the carpenter!"

Enlil’s response was as cold and unyielding as a winter storm. He stood as the guardian of cosmic order, and Inanna had willfully violated it. "Your queen went to a place of inviolable laws," he declared, his voice devoid of pity. "She sought dominion over the Great Below, a realm with its own rites and traditions. The one who enters the underworld does not return. How could I expect her to be an exception? She knew the rules and must now face the consequences." He offered no help, turning his back on Ninshubur’s pleas.

Dejected, Ninshubur went to the moon god Nanna, who also refused to interfere. Finally, she reached Eridu and pleaded with Enki, the god of wisdom and magic. Unlike Enlil, Enki was moved by compassion and a love for his brilliant daughter, Inanna. He took dirt from under his fingernails and fashioned two small, clever creatures. He gave them the food and water of life and sent them to the underworld with a plan to trick the grieving Ereshkigal and revive Inanna. The plan succeeded, and Inanna was restored to life.

However, the laws of the underworld that Enlil had so sternly defended could not be so easily cheated. Inanna could ascend, but she had to provide a substitute to take her place. Escorted by the ghoulish demons of Kur, she returned to the world of the living, searching for a replacement. When she found her husband, the shepherd-king Dumuzid, celebrating in her absence instead of mourning her, her fury erupted. She chose him, and the demons dragged him down to the Great Below.

Symbolism and Meaning

For the ancient Sumerians, this epic story was rich with symbolic meaning. Inanna’s descent and return were deeply connected to the agricultural cycle. Her death represented the dormant season when the earth is barren, while her resurrection symbolized the return of fertility and life in the spring. The subsequent descent of her husband, Dumuzid, was tied to the oppressive heat of the late summer that withers vegetation.

The story also served as a profound exploration of the limits of power. Inanna, the mighty Queen of Heaven, learns that her authority is not absolute. In the face of death, she is rendered completely helpless, a powerful lesson for a society that both revered and feared its divine rulers.

Enlil’s role is particularly significant. His refusal to help was not born of malice, but of a commitment to universal order. It represented the ancient understanding that there are fundamental laws in the cosmos—like the finality of death—that cannot be bent, even for the gods. He symbolized the necessary, albeit sometimes harsh, structure that prevents the universe from descending into chaos. In contrast, Enki represented the power of cleverness, compassion, and ingenuity to find solutions within the confines of those rigid laws.

Modern Perspective

Today, the myth of Inanna’s descent continues to captivate scholars, writers, and artists. In cultural studies and feminist literature, Inanna is often interpreted as an archetype of female empowerment and autonomy—a figure who dares to explore the darkest parts of existence to emerge with greater wisdom. Her story is seen as a "heroine’s journey," a counterpart to the traditional male-centric epics.

Her influence can be seen in modern media, though often indirectly. Characters in fantasy novels, video games (such as Ishtar in the Shin Megami Tensei series or various god-based games), and comics draw from her complex persona as both a creator and a destroyer. Scholars study the myth not as a literal account but as a priceless artifact of human consciousness, revealing how an ancient society grappled with the universal mysteries of life, death, and rebirth.

Conclusion

The story of Inanna’s descent and Enlil’s unyielding oath to cosmic order is a testament to the sophisticated storytelling of the ancient Mesopotamians. It is a cultural treasure, a myth that sought to explain the world and the human condition through a vivid, imaginative narrative. It is crucial to remember that these are foundational stories from a specific cultural heritage, not accounts of reality or articles of faith.

As Muslims, we recognize that only Allah is the true Creator and Sustainer, the sole power in the universe, and these mythological tales are products of human imagination from a time before the final revelation. Yet, in studying them, we gain a deeper appreciation for the long and varied history of human culture. These myths reflect the timeless quest for meaning, the power of storytelling to make sense of a mysterious world, and the enduring imaginative spirit that connects us to our most distant ancestors.